ALEXANDER R. MALAKET, CITP, reviews developments in the MENA region regarding the risk dimension of international trade finance.

Just as trade finance has emerged from the stillreal economic crisis with greater profile, the importance of risk assessment and mitigation have been effectively highlighted by the realities of the crisis. at the same time, political events in MENA and elsewhere have brought into focus the fundamental importance of sovereign risk in international business

Trade financiers – as well as business leaders, from small-and-medium enterprises to large corporates – forgot for a time that effective risk assessment and mitigation are core elements of the value proposition of international trade finance.

In the context of so-called “traditional” trade finance instruments, the textbook distinction between documentary credits (best suited to transactions involving new or unproven trading relationships and/or high risk markets) and documentary collections (trusted relationships, stable markets) was lost and rendered nearly irrelevant in many parts of the world.

While this may have been less the case in the Middle East, it remains true that this trend was widely observed in the two or three years before the eruption of the global crisis, at least in part as an outcome of demands from large retailers seeking to conduct trade on less expensive open account terms.

This unfortunate disregard for adequate risk assessment and risk management was evident in transactions involving markets that would have otherwise been considered relatively risky; similarly, importers and exporters establishing new trading relationships even in such higher risk markets frequently agreed to conduct business on terms that, effectively, disregarded the realities of risk in international commerce.

In parallel, the role and value of export credit and insurance agencies were brought into question in many markets across the globe, further diluting the necessary focus on risk assessment and risk mitigation by diminishing the importance of this aspect of the activities of export credit agencies (eCas) in international commerce. The critically important and fundamental nature of the role of eCas in enabling and supporting international commerce has been recognised and reinforced as a direct result of the global crisis and, by extension, their ability to contribute to effective risk mitigation in international commerce has been preserved for the foreseeable future.

Risk has always been and shall always be a reality in the conduct of cross-border business. That truth has once again been recognised.

A View of Risk

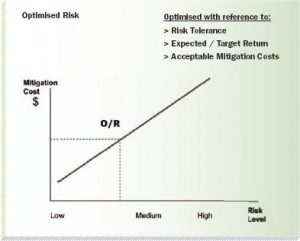

Specialists in international trade and international business appreciate that risk is meant to be understood, assessed and appropriately mitigated or optimised. risk cannot in general be completely eliminated nor should it be fatalistically ignored. risk is intimately linked to return, and can serve as an effective de-motivator to potential competitors.

This notion of risk optimisation is in no way intended to imply a casual approach to risk analysis and assessment. On the contrary, it follows, by definition, that successful optimisation of risk is the outcome of due diligence, appropriate transparency and skilled, effective analysis, balanced against expected returns and costs of mitigation.

Understanding that financial and commercial transparency continue to evolve in the Middle East – as in other parts of the world – it is worth considering a similarly evolving view of risk that might apply in a region long recognised for its business acumen and commercial prowess.

A “return to fundamentals” and banking, financial services and business more broadly has been promoted and championed in many markets across the globe, though it has been argued that the Mena region has remained generally focused on those fundamentals in a disciplined manner. Yet there have been indications of a loss of focus on the risk dimension of international commerce and international trade finance.

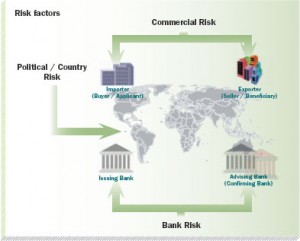

Sovereign, Bank & Commercial Risk

Sovereign or so-called political risk rejoins bank risk as a key consideration in a well-devised and well-considered risk assessment and mitigation process, in no small part due to the turmoil that has gripped several countries in the Middle east and north africa over the past few months. The very real human, economic and commercial implications of a significant shift in sovereign risk dynamics could not be more clear – and the im- plications for trade finance reverberate through the region and beyond.

Adequate analysis and assessment of mediumterm conditions will be best served by a combination of global view and local, intimate knowledge of the markets under consideration, with the all-important regional view included for good measure.

In addition to illustrating the very real, practical and relevant impact of political and sovereign risk within a particular market, conditions in the Middle east and north africa have demonstrated the way in which political instability can travel across borders in what amounts to an instant – fuelled by accelerant communication through social media and other technologies.

To be clear, there is no value judgment attached to political instability or civil unrest in a given  circumstance or a given set of circumstances here – merely the observation that such instability generates very clear and very tangible commercial consequences. Those implications touch even short-term trade obligations, generally viewed as relatively secure in times of economic difficulty, and will certainly impact macro-dynamics such as perceptions about the climate for existing investments (security of assets) as well as planned/ future investment.

circumstance or a given set of circumstances here – merely the observation that such instability generates very clear and very tangible commercial consequences. Those implications touch even short-term trade obligations, generally viewed as relatively secure in times of economic difficulty, and will certainly impact macro-dynamics such as perceptions about the climate for existing investments (security of assets) as well as planned/ future investment.

The bank or financial sector level of the risk discussion has been amply addressed on a global basis in the context of the crisis and recession, with businesses across the MENA region losing confidence, albeit temporarily, in international institutions, and local firms championing the importance of direct client engagement and deep knowledge of the region. The positive impact of Shari’a Law on financing – in particular trade finance – has been widely recognised, as much for its basis in fundamentals as for a direct linkage to an underlying asset, aside from other merits.

An important nuance in markets across the MENA region is the frequently close connection between sovereign and bank risk, due to state or state-linked ownership of the financial sector – a reality that extends well into the commercial relationships through similarly integrated ownership models. One parallel is the relationship of staterun export credit agencies and the impact this has on their own risk profile (effectively equivalent to the risk standing of the country which the ECA serves), as well as their ability to secure funds at favourable rates (on the “national credit card”), all the while engaging, goes the argument, in business on non-commercial, unsustainable terms.

Commercial risk, typically involving buyer and seller, but, perhaps, also intermediary parties and/or affiliates, is a reality in any business transaction, though its risk profile is typically amplified in cross-border transactions where visibility and transparency – and an absence of information about counterparties – tend to be more important, and often less available than in domestic commercial relationships.

Transparency in this context extends beyond the still fundamental issue of financial transparency and reporting, to (appropriate) transparency about commercial operations, and active efforts to manage market expectations through adequate flows of information – a lesson that was illustrated in a high-profile manner several times over the course of the crisis.

Risk Transfer

The ability to “enhance” risk, through insurance and guarantee solutions, or through the transfer of risk from one context or party to another, is a long-standing aspect of the value proposition of international trade finance – and one which, like the subject of risk, has again regained profile in discussions related to trade finance.

Issuing a documentary credit involves credit enhancement/risk transfer to the extent that the issuing bank’s profile is favourable in comparison to that of the importer – providing comfort to an exporter about the higher probability of settlement as agreed. Similarly, confirmation of a letter of credit by a confirming entity (typically) in the home country of the exporter represents risk transfer in several respects: a confirmed LC removes, from the exporter’s point of view, the issue of sovereign or country risk, just as it replaces issuing bank risk with confirming bank risk, and commercial (importer) risk with confirming bank risk, provided all documentary terms and conditions have been fully complied with.

More recent trade finance instruments and mechanisms, including various flavours of supply chain Finance, have incorporated risk mitigation and risk transfer/credit enhancement options in their structures, at times shifting risk between parties in a particular global supply chain.

Whether supply chain finance programmes are relatively basic, such as invoice financing, or whether they are comprehensive, multi-party or multi-bank programmes reaching into massive, extended supply chains certain fundamentals around risk management, risk transfer and credit enhancement are being integrated at the transaction and technical platform level. They also remain within the parameters of global supply chain finance programmes.

Given the new commercial realities of the moment in international commerce, it is both appropriate and necessary, for new modes of financing to include risk mitigation features and risk transfer options. Both act as an element of the evolving value proposition around trade finance, and as a means of facilitating relatively efficient use of capital through risk transfer and credit enhancement.

Reputational Risk

Just as it is acknowledged that financiers in the MENA region have, by and large, remained in alignment with “fundamentals” in financing, it is true that a dimension of risk which has been the focus of some attention in certain markets since the crisis (notably the US.and Europe). However, the central role of this particular type of risk has been a well understood for hundreds of years – or, perhaps, several thousand – in the Middle East. Reputational risk – the impact of negative association to a financial institution, to a client or counterparty, or a particular international transaction – has reached centre-stage in terms of profile in certain organisations. Encompassing dimensions such as ethical conduct and technical skill or competence among other factors, it has become an imperative with profile up to the level of the chief executive.

In the Middle East, the long-established practice of “name lending” relies heavily (in some cases, almost entirely) on the notion that reputational risk exerts sufficiently powerful influence to assure appropriate and trustworthy commercial behaviour.

While this practice has been criticised as lacking robust disciplines linked to credit and risk assessment, and international institutions have been advocating a reduced emphasis on “name lending” (with some recent developments in the region providing supporting evidence), it is worth noting that there is a convergence of sorts. There appears to have been a shift to more “objective” risk assessment practices in certain markets in the MENA Region, coupled with a parallel broadening in focus to include greater consideration of reputation and reputational risk among financial sector organisations (and their clients) in markets from the Americas to Europe and beyond.

Risk & Capital

Another dimension of risk inexorably gaining profile and priority is related to the use and application of capital in the context of a trade or supply chain finance transaction.

While the MENA region is not yet fully engaged in terms of implementing the latest Basel capital reserve requirements – and the nature of those requirements remains the subject of vigorous discussion – it is a foregone conclusion that capital adequacy must become a far more central element of the risk discussion. This should be both within financial institutions as various lines of business compete for financial resources and with clients, in order to engage in proactive, joint efforts to structure trade finance transactions with appropriate focus on the capital implications of the various options available.

The risk/capital discussion must evolve into a core element of the dialogue between financier and client, and more broadly, across increasingly global and complex supply chains. The MENA region is well-placed to prepare a foundation for such dialogue as part of the implementation and rollout of the BIS requirements eventually approved.

Such dialogue will be most effective if it engages local financial sector regulators, as well as other parties perhaps less obviously impacted by the evolution of regulatory requirements, including export credit agencies, private sector risk insurers and others with a stake in the optimal functioning of trade and supply chain programmes.

Finally, one reality permeates every dimension of the discussion around risk and trade finance. Parties with an interest in the efficient enablement of international commerce must engage actively to understand, optimise and communicate appropriately about the risk universe in international trade finance – particularly as commercial realities evolve and trade and supply chain finance solutions evolve in consequence.

Cash And Trade Magazine For Cash and Trade professionals in the Middle East

Cash And Trade Magazine For Cash and Trade professionals in the Middle East