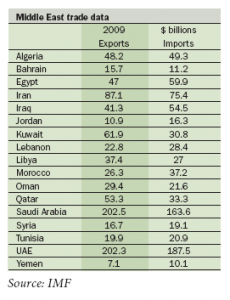

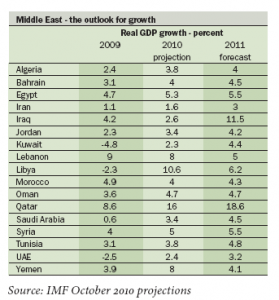

Recovery is under way, in the oil-rich Gulf states certainly, and more tentatively across other parts of the Middle East and North Africa. And trade is central to this revival, as the resurgence in global economic activity lift s international demand for the region’s oil, gas and heavy industrial exports such as petrochemicals and aluminium.

But the pace is still tentative. And there is a risk that the benefi ts of new growth will be unevenly spread and will fail to translate into employment and public prosperity on the scale that might have been hoped for.

For many parts of the Middle East still have major challenges to overcome in terms of trading competitiveness, as the International Monetary Fund has just pointed out in its economic outlook for the region.

“Enhancing competitiveness will be key for the region’s ability to grow faster, create more jobs and fully reap the benefi ts of globalisation. This will imply improving the quality of education, developing a more favourable business environment, and deepening and diversifying trade flows,” says Masood Ahmed, director of the Middle East and Central Asia department at the IMF.

The challenge is to develop a wider range of products and services to complement the hydrocarbons sector on which many Middle Eastern states remain over-reliant as a driver of exports and economic output.

Drawing on the latest data from individual countries, the IMF is projecting a 3.5 per cent rise in oil sector GDP in the region this year, with 4.3 per cent forecast for 2011.

By contrast, it believes that over the two years from 2009 to 2011, the GDP of the Middle East’s non-oil economy will have risen by just a single percentage point. Moreover, although oil output is rising, reaching 25 million b/d this year and with expect

ations of reaching 26 million b/d in 2011, much of the rise in the value of oil GDP is explained by the rebound in oil prices – something that is useful in current circumstances but is largely outside the control of the exporting countries.

More diversification needed

The other drawback of over-reliance on oil and gas is that these industries are not labour intensive. Although many workers – and in Gulf states these are usually foreign migrants – are employed in constructing the big hydrocarbon projects, once the new plants are in operation they offer few permanent jobs for either locals or foreigners.

So if Middle Eastern economies are to provide work for their populations – which are growing faster than in almost any other region of the world – they need to diversify their production and trading base.

The recent IMF-World Bank joint annual meetings have provided a chance for policymakers from the region to review these issues with staff from the Bretton Woods institutions. But the problems are mostly not ones that can be quickly resolved through an injection of external assistance or technical expertise.

They have to be tackled through far-reaching and sustained reforms to the structure of the region’s economies and the way they are regulated.

For example, the IMF points out that many of the region’s economies are still burdened by rules that are heavily bureaucratic. In a number of countries, the limits on the scale of foreign business ownership remain tight.

A year ago the World Bank complained that reforms designed to create more scope for private enterprise were often implemented in an “unequal and unpredictable” manner. The Bank’s survey research found that almost 60 per cent of all business managers in the region felt that rules and regulations were not applied consistently or predictably.

There is little to suggest there has been major progress over the 11 months since the Bank expressed its concerns.

In effect, some businesses benefit from privileged treatment; rules are applied in what the Bank describes as a “discretionary” way. But, of course, this puts other companies or investors at a relative disadvantage, and the overall impact, therefore, is to hold back economic growth and job creation.

For example, in many Middle Eastern countries foreign investors still do not feel they will get equal treatment before the courts if they become involved in some form of business dispute with a local counterpart.

The process of reforming the business environment is a slow one. But progress can be made. Kuwait already has a tradition of judicial independence; and in both Dubai and Qatar independent authorities have been set up to provide international standard regulation for key sections of the financial sector.

Similarly, there are markets in the region that have shown how it is possible to diversify and develop a strong competitive trading position in sectors other than oil and gas.

As Masood Ahmed pointed out: “Tunisia, for one, stands out as having become an ‘outsourcing hub.’ It has successfully attracted foreign direct investment in textile production, car assembly and food processing over the past several years and, more recently, in information technology and aeronautics.

“Simplified regulation, modern infrastructure, government incentives, and commitment to a knowledge- based economy that generates well-trained, low-cost workers are key factors in this success.”

And, despite its recent financial problems and overreliance on real-estate projects, Ahmed believes that Dubai still stands out as an example of how to develop an internationally competitive economic position as a logistics hub, and centre of international trade and related services.

Meanwhile, both Morocco and Egypt have managed to sustain steady growth throughout the global downturn of the past two years.

Partly this has been achieved through the development of a varied domestic economic base – for example, the expansion of the Moroccan urban middle class has generated domestic demand for housing, transport and consumer goods.

Key supports to trade

But these countries’ success is not a purely internal phenomenon. Egypt has proved strikingly successful in broadening its export base into sectors such as petrochemicals.

One of the factors that has helped to make such economies more competitive in international trading terms is actually the reduction of barriers to imports from abroad. It may seem paradoxical but Egypt and Syria have improved their own export performance by reducing tariffs on incoming foreign goods; this has reduced the cost to their own companies of buying in foreign technology and components.

As in the West, enhancing access to finance is also a key support to trade development. If local companies can raise extra working capital and trade finance at affordable rates, this obviously makes it easier to fund modernisation and to extend attractive trading terms to foreign buyers.

This could be particularly important for the Gulf Cooperation Council states – Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Oman and Bahrain – which are in the process of creating a regional single market.

They have exploited their oil and gas reserves to establish a strong position in energy-intensive heavy industries such as aluminium, petrochemicals and steel. But progress in carving out an export niche for “downstream” manufactured products has been much slower – with a few exceptions. (For example, Ras Al- Khaimah, in the UAE, has become an internationally important producer of domestic ceramic goods such as such as tiles and sanitary ware.)

But there is now a renewed effort to identify areas where Gulf countries can remain competitive while still providing the high living standards to which many of their citizens have become accustomed.

Abu Dhabi is, perhaps, the leading pioneer in this respect, investing heavily in the development of niche heavy industries such as high-tech shipbuilding and even aerospace, in partnership with leading international companies in these fields. Initially, the strategy was greeted with some scepticism by outside commentators; but the evidence suggests that in some specialist areas, such as the construction of specialist patrol craft to protect offshore oilfields, the emirate is beginning to establish a competitive position.

Other Middle Eastern countries will need to follow such innovatory examples if they are to achieve the trade diversification that remains essential to reducing the region’s still heavy reliance on oil and gas.

Cash And Trade Magazine For Cash and Trade professionals in the Middle East

Cash And Trade Magazine For Cash and Trade professionals in the Middle East