Export credit agencies are continuing to provide strong support to MENA projects as well as supplying classic trade financing products to the region. MELANIE LOVATT reports

While there was no Sadara deal this year – last year export credit agencies (ECAs) provided more than 50 per cent of the giant $20bn Saudi Arabian petrochemical project’s $12.5bn debt – they stepped up with funding on other multi-billion dollar schemes.

The conditions that have led to the increase in use of ECA funding have largely continued unabated. Foremost, as the cost of projects has increased in a push for economies of scale by sponsors, more sources of debt must be tapped.

The high cost of materials and services has also led to big price tags on engineering, procurement and construction contracts, so project sponsors and their advisers have looked to raise money from as many pools as possible. This has often encouraged them to tailor their contracting and procurement, where possible, to countries where ECA funding can be secured.

ECAs were needed to cover shortfalls in project funding after the ill-effects of both the 2008 global financial crisis and the European debt crisis. They stepped up to the plate and their use became more widespread on projects around the world, as international lenders pulled back. Of course, the increase in funding and cover was not simply altruistic. When their host countries were hit by unemployment, ECAs were directed by their respective governments to fund equipment and technology exports to help support jobs.

While some international banks remain troubled, most lenders have recovered from the global credit crunch, and are eagerly seeking new deals. But ECAs are still finding that their services are very much required. “Projects are simply becoming way too large to just use the banks to push them through,” said one project finance expert.

Also, while many international lenders are coming to terms with the new Basel III regulations that will come into full force in 2019, others are still concerned about being over-committed given that the new method of accounting will push banks to apply more capital to longer-tenored loans. This includes project finance, where tenors can typically stretch out to 12-16 years and by as much as more than 20 years for independent power projects (IPPs) and independent water and power projects (IWPPs).

ECAs have also ushered in changes that have made sponsors more willing to include them in project financings. Many of them have increased direct lending, in addition to providing typical ECA cover. Also, some have relaxed “local content” requirements if they see an advantage for their host country in supporting a certain project (see Cash and Trade September/October 2013).

Japan’s ECA, the Japanese Bank for International Cooperation, will often support energy projects in order to gain access to oil and gas resources and shore up its energy security and provided a $3bn loan to the state-owned Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (ADNOC) in the first quarter of 2013, which was the third $3bn Japanese facility it has arranged since 2007. The ECA has also supported a number of UAE projects.

The time it takes for ECAs to conclude project financings has been cut in recent years, which has acted to increase demand for their services. They used to be very slow compared to banks, say project advisers, but they have now streamlined their approval processes for deals.

However, project experts note that the key to pushing the financing through successfully is still to engage ECAs early in the process in order to use them to help structure deals. “If a deal is accepted by the ECAs, you will generally find that it meets the approval of banks and their credit committees,” explains a European banker who lends to MENA projects.

Notable billion-dollar deals

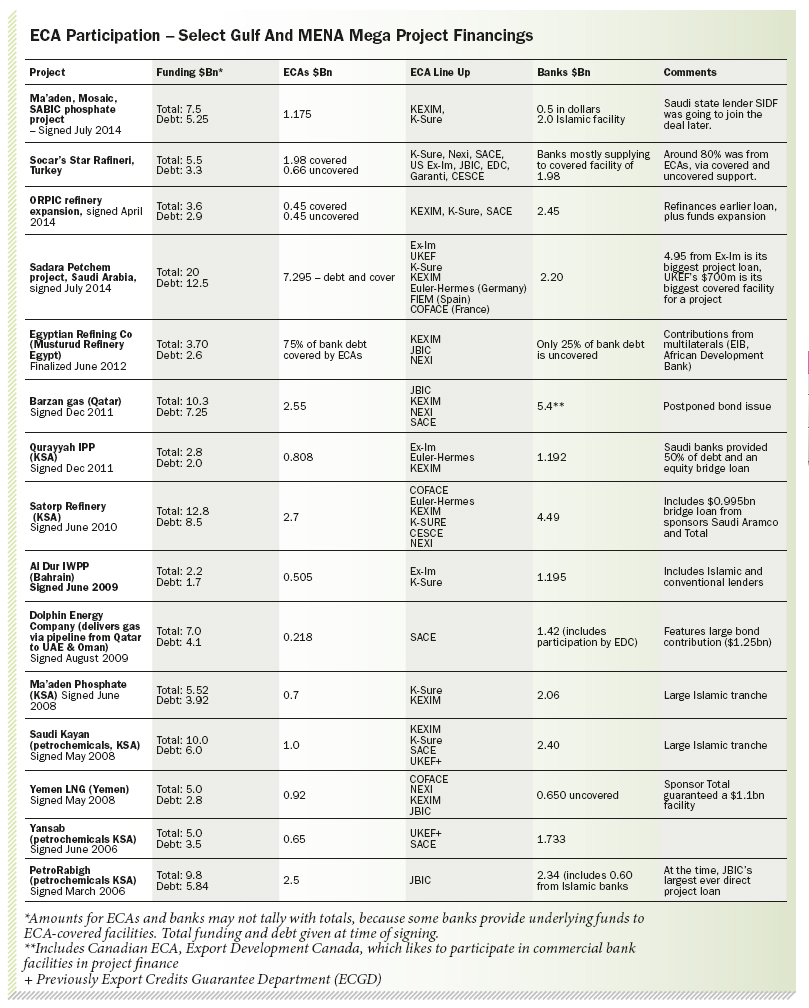

Notable deals featuring ECAs so far this year in the Gulf include the $7.5bn phosphate project sponsored by Ma’aden, mosaic and petrochemical giant Saudi Basic Industries Corp (SABIC). On a $5.25bn financing, Korean ECA Kexim provided $775m, comprised of a $600m direct loan and $175m covered facility to which banks supply the underlying funding (see table). Fellow Korean ECA K-Sure supplied a $400m covered facility. Aside from this, Saudi institutional lender the Public Investment Fund (PIF) contributed $2bn, with international banks supplying $500m of loans in dollars while there was also a SR7.5bn ($2bn) domestically provided Shari’a compliant facility.

Other Saudi projects are poised to look for funds. They include joint venture partners Saudi Aramco and Sumitomo, which are expanding their Petro Rabigh refinery. The $5.84bn debt financing for the $10bn phase 1 of the project ,which was signed in 2006, saw JBIC supply $2.5bn.This was its largest ever direct project loan at the time. The phase 2 financing is likely to feature input from JBIC, and, possibly, other ECAs.

Azeri company Socar saw a high percent of funding come from ECAs. They have provided around 80 per cent of the $3.3bn debt for its $5.5bn Star Rafineri project. Six of them have stepped up, with $1.98bn coming from covered facilities and $660m from direct loans. Oman Oil Refineries and Petroleum Industries Company (ORPIC) completed a $2.9bn funding in April. This will repay some $1bn from an earlier loan used to fund construction of its Sohar refinery and expand it by about 70 per cent to give a throughput capacity of 198,000 barrels per day of crude. On this deal banks stepped up to provide about $2.4bn, with Kexim providing about $450m of uncovered funding and K-Sure and Italy’s SACE supplying a $450m covered facility.

ORPIC is also looking to develop its planned Liwa Plastics project, which has a price tag of around $3.6bn. That deal is also expected to feature a combination of banks and ECAs. Further funds will also be needed for the Duqm refinery project, which is a joint venture between the Omani government and Abu Dhabi’s IPIC. With its $6bn price tag, this scheme will need to tap all available funding, including ECAs.

Another large project, this time in Qatar plans

to include ECAs on its financing. The $6.4bn al-Karaana petrochemical project being implemented by Qatar Petroleum and oil major Shell is expecting to see support from the Export-Import Bank of the US (US Ex-Im), JBIC and Kexim. Information is expected to be launched to a wider bank group in the autumn.

ECAs will also be asked to supply funding for an array of power projects that are being implemented across the Gulf in order to meet growing demand from the region’s expanding industries and growing population. Again, the sheer size of many of these schemes necessitates tapping multiple pools of funding.

However, when it comes to projects in the wider MENA region, particularly countries beset by instability, such as Egypt, ECAs and multi-lateral lenders are needed in order to protect against political and other types of risk.

In Egypt, the 2,250 megawatt Dairut IPP sponsors will seek to attract bidders in September. The project has been in the planning stage for some time, seeing protracted delays as a result of the political turmoil. A number of multi-lateral lenders have provided letters supporting the project, including the Islamic Development Bank, African Development Bank, World Bank and its private lending arm the International Finance Corp (IFC) and European Investment Bank. They will all be needed to get the financing out of the gate, and ECAs are very likely to be asked to provide support by the bidding consortia.

Trade finance support

In addition to stumping up large swathes of funding for the region’s projects, ECAs have offered reliable and sometimes creative support for MENA trade finance. Export Development Canada agreed in June to provide a $200m Islamic vendor financing structure to Saudi Arabia’s Mobily to help it acquire telecommunications equipment from Alcatel-Lucent. It has also provided a $10m credit line to Turkey’s Aklease, to help it lease equipment from Canadian companies, which is aimed at SMEs.

For Saudi Arabia’s Mobily, two Nordic ECAs have provided Shari’a compliant finance. Finland’s Finnvera and Sweden’s EKN have agreed to provide SR2.1bn ($560m) financing for sourcing of telecommunications equipment from Ericsoon and Nokia Siemens Networks. With a ten-year payback period, the facilities pay a 2.4 per cent fixed interest rate per annum.

US Ex-Im is looking to provide funding to Iraq for its purchase of around $2bn of Boeing jets, while JIBC will finance in part a buyer-credit loan for the Iraqi Ministry of Electricity to fund electrical substation construction. The facility totals around Yen 50bn ($490m) with JBIC to supply about 60 per cent and the remainder coming from other lenders. However, although a deal was signed in early 2014, it looks as if the recent and worsening instability resulting from attacks by Sunni jihadist militia in the country will impact the timetable for funding and implementing development projects.

ECAs that operate from within the Gulf are also extending their business lines, and countries without ECAs are looking at the possibilities of creating them in order to boost financing in the Arab world and to customers seeking Shari’a compliant trade funding structures. Dubai is looking to set up a “Dubai Ex-Im Bank” and has mandated Noor Investment Group to study the possibility; and Oman’s Export Credit Guarantee Agency has signed an MOU with the Al Rafd Fund to provide credit insurance and guarantees to SMEs.

ECAs will continue to follow their usual line of business in MENA, which is supplying trade finance, but they will also remain a mainstay for project funding, given the mounting cost of planned projects. These are aimed at implement infrastructure upgrades, and, in the case of the Gulf, allowing countries to move downstream from crude oil production and increase the value of their exports.

However, although capital markets are expanding, particularly the Sukuk sector in Saudi Arabia, stock and bond markets need to develop further before they are able to supply a meaningful chunk of the cash needed to finance all of this activity.

As a result, local and international banks will remain a key provider of project funding, but, unless their liquidity increases markedly, project sponsors will continue to rely on ECAs.

Cash And Trade Magazine For Cash and Trade professionals in the Middle East

Cash And Trade Magazine For Cash and Trade professionals in the Middle East