will process 400kbpd Arabian

heavy and medium crude

As the US limbers up to become the world’s largest oil producer by 2015 thanks to fracking, OPEC members are confident that they can ride out the competition. MELANIE LOVATT looks into the future

Glf oil producers reaped the benefits of sustained high crude prices in 2013, enabling most of them to enjoy budget and current account surpluses accompanied by healthy trade balances.

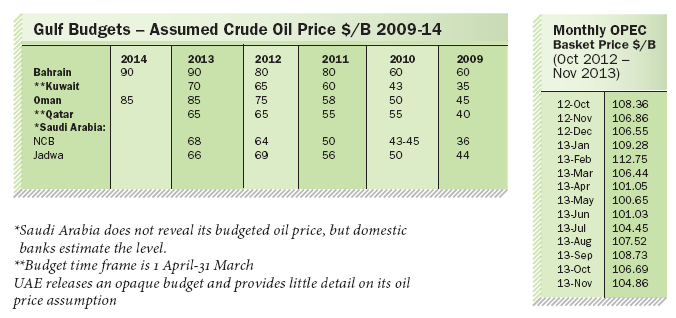

Although the OPEC crude oil basket price edged down from the highs of more than $110 per barrel it hit in September, its staying stubbornly lodged above $100/B in the fourth quarter, thawing relations between the West and Iran, having been a cause for optimism.

This takes on greater significance because Gulf producers’ reliance on a high oil price has increased over the past few years as government expenditure has surged in response to social pressures further heightened by the regional unrest of the Arab Spring.

Global economic growth is picking up, but at a tepid level, and a faster-than-anticipated rise in oil and gas production from North American hydraulic fracturing (fracking) of shale deposits is a cause for concern. Gulf producers (of which Saudi Arabia, UAE, Kuwait and Qatar are OPEC members) believe they can “ride out this storm”, which will see the US emerge as the world’s largest oil producer by 2015. OPEC said that while the “call” on (demand for) its crude will fall year on year until 2017 to 28.8m barrels per day (b/d) versus current levels of 30.3m (b/d), it expects

to see a marked uptick by 2020 as shale oil production reaches a plateau.

OECD energy watchdog the International Energy Agency (IEA) agrees, suggesting that while non-OPEC supply will play a major role in meeting oil demand growth this decade, OPEC will play “a far greater role after 2020”. It is unsurprising, therefore, that Gulf producers are spending considerable sums on maintaining or trying to increase crude production capacity. Ratings agency Standard & Poor’s sees a limited impact in the shale surge due to the ability of Gulf producers to “redirect oil exports” and the fact that many of them export heavier crudes not displaced by lighter shale production. But over the longer term S&P warns that shale production could cut into the Gulf’s market share.

Gulf producers are also faced with a rebound in Iranian production. Iran struck a defiant note at the 4 December OPEC meeting in Vienna, suggesting it would hike output regardless of oil price. Tehran is seeking to return production from the current 2.4-2.7mn b/d (opinion is divided on exact figures) to pre-EU sanctions levels of 3.5-3.7mn b/d and ultimately wants to raise it to just above 4mn b/d. It reached a six-month interim agreement with Western powers on 24 November in Geneva to restrict its nuclear industry in return for relaxing sanctions. While Tehran is in talks to lure back international oil companies, sanctions will not be lifted immediately, and it will take some time to secure the equipment needed to implement the planned increases.

If Iranian production does bounce back, it could be at Saudi Arabia’s expense. This OPEC powerhouse maintained its status as the world’s pre-eminent swing supplier in 2013 and boosted output to make up for reductions from Iran and other countries. And there are signs that in the year ahead 2013’s disruptions in Nigeria, South Sudan and Libya could continue. Iraq could also struggle to maintain higher levels. It became the second largest OPEC producer when Iran’s output tumbled and it is unrestricted by OPEC quotas. But its impressive production increase saw setbacks as 2013 wore on with the security situation worsening, and hostilities spilling over from neighbouring Syria.

There are also growing concerns that large swathes of the Middle East could be torn apart along Sunni-Shia lines, with part of that rift running through Iraq.

Rise in spending on projects

With OPEC deciding to roll over its 30m b/d production ceiling at the recent meeting and some OPEC and non-OPEC producers struggling to maintain output levels, at least for the interim, Saudi Arabia is expected to continue its role as a market-balancer. State producer Saudi Aramco has been using enhanced oil recovery techniques to keep capacity around 12.5m barrels/day, which provides a comfortable cushion of supply above current production levels that could be brought on line if needed.

The Joint Organisations Data Initiative (JODI) put the Kingdom’s September 2013 production at near historic highs of 10.123m barrels/day, versus the 9.753m barrels/day produced a year ago. Significantly, despite climbing domestic consumption, exports rose to 7.844m barrels/day in September 2013, according to JODI. This is the highest level Saudi Arabia has seen since November 2005 when it exported 7.962m barrels/day. OPEC’s November monthly Oil Market Report put the Kingdom’s October 2013 production (citing secondary sources) at 9.839 b/d, down from 10.049 b/d in September, or (based on direct communication) at 9.753 b/d in October and 10.123 b/d in September.

Despite being a great export earner, oil is not an employment intensive industry so the Kingdom is targeting sustainable economic growth by diversifying downstream into petrochemicals and plastics, and other industries. As a result, capital spending on projects (especially in the petrochemical and infrastructure areas) has climbed in the past few years, boosting imports of equipment.

Dominated by oil exports, the trade balance has stayed positive, but the value of letters of credit (LCs) signed by importers also remains high amid good demand for building materials and consumer goods. The latest figures from the Saudi Arabian Monetary Agency (SAMA) showed that opened LCs for private sector imports financed through commercial banks for September 2013 were at SR17.6bn ($4.7bn) versus the year-ago level of SR16.8bn ($4.5bn). Settled LCs were at SR21.9bn ($5.8bn) in September 2013 compared to SR21bn ($5.6bn) in September 2012.

Opened LCs had surged to SR204.3bn ($54.5bn) in 2012 which is up 15.9 per cent from the previous year, and an all-time high. Settled LCs were at SR253.7bn ($67.6bn) in 2012, up 12.9 per cent from 2011 and also a record high, according to SAMA data. From figures reported thus far it appears that 2013 will come close to matching 2012’s levels. From January through to the end of September they were at SR150.9bn ($40.2bn) (opened) and SR190.6bn ($50.8bn) (settled).

However, Saudi Arabia’s crackdown on illegal foreign workers, which began with the expiry of an amnesty in November, has already started to affect the construction sector. How significantly will not be clear until the fourth quarter GDP numbers are released in early 2014, notes James Reeve, deputy chief economist at Samba. He sees Saudi Arabia’s economy continuing to expand, but at a slower rate. “Saudi Arabia’s position remains far from serious but will be more constrained than in recent years,” he warns.

Banking sector relies on oil

Saudi Arabia’s banking sector was expected to post good earnings from a growth in trade and corporate lending for 2013, even though it appeared unlikely to match 2012’s stellar performance. “High oil prices are absolutely supporting the banking sector,” said Said Al-Shaikh, chief economist at Saudi Arabia’s National Commercial Bank. “Whatever money is being spent is coming to the banking system via wages or payments to contractors,” he explained.

“As a result, we’ve seen a continued increase in deposits and in turn banks have more capacity to lend. Banks rely on this money being injected into the economy and it is captured in the banking system in the retail, corporate and treasury sectors,” he said, emphasising that oil earnings are vital to the profitability of banks in the Kingdom.

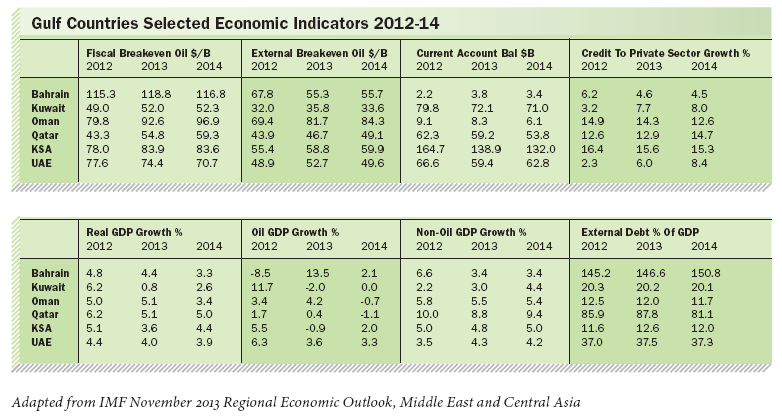

But while 2013 was a good year, NCB forecasts real GDP coming off slightly, at three per cent, down from 2012’s 6.8 per cent and 2011’s 8.5 per cent. The IMF puts 2012 real GDP at 5.1 per cent, at 3.6 per cent for 2013 and 4.4 per cent for 2014 (see table).

Despite Saudi Arabia’s diversification efforts, crude oil still generates a whopping 90 per cent of state revenue. However, the Kingdom has prudently managed its resources over the last several years, paying off debt and building up reserves. Net foreign assets parked at SAMA, the country’s central bank, currently total around $713bn. This gives it more breathing space than many other oil producing countries. Saudi Arabia’s fiscal breakeven price for 2013 was projected by the IMF at $83.9/B (see table) which is well under the $105/B average price at which Saudi Arabia sold its export grade, Arab Light, during the year.

However, as a result of its extra budget spending, implemented in the wake of the Arab Spring, the Gulf’s most populous country – it has 30m inhabitants – has seen its fiscal break-even price trend upwards over the last few years. In the Gulf only Oman and Bahrain have higher break-even oil prices, but oil production of these two non-OPEC countries is much lower than their neighbours.

For Saudi Arabia, Qatar, UAE, and to a lesser extent Oman, 2013 was a year of consolidation, albeit from high levels, while Bahrain and Kuwait continue to follow expansionary fiscal policies. All the GCC countries continue to run relatively large overall fiscal surpluses because oil revenues remain high, except Bahrain which is in deficit and carrying a large debt load. The IMF warned in its November 2013 report that a sustained period of oil prices $25/B under the $90/B baseline needed by most MENA oil producers to balance their budgets at estimated production levels would lead to deficits from 2015 for all except Kuwait and the UAE.

Call to reduce expenditure

But while Kuwait may appear to be in an enviable position its prime minister, Shaikh Jabir al-Mubarak al-Sabah, finance minister Shaikh Salim Abd al-Aziz al-Sabah and IMF officials all called for a reduction in spending. Even though the country’s budget has ended with a surplus for the past 15 years, there are concerns that it lacks the ability to produce wealth, with many of its people relying on what is viewed as a “welfare state”.

This is seen as unsustainable if oil prices show a protracted drop. Kuwait has tried to increase oil production, implement petrochemical projects and expand its refinery sector, but contract awards have been derailed by political opposition and corruption allegations. This political wrangling, which has caused governments to come and go in a virtual revolving door, and the cancellation of a planned $17bn project with US petrochemical giant Dow will make it difficult for Kuwait to attract international participation.

The country is now aiming to increase its crude oil output capacity from current levels of almost 3m b/d to 4m b/d by 2020, but its track record in keeping top officials in the job long enough to accomplish anything invites scepticism.

Towards the end of 2013 Kuwait launched a $4.2bn engineering, procurement and construction tender for the heavy oil development at its Ratga field. This will be significant for the country’s oil production capacity expansion. But it recently pulled out of the development of the Neutral Zone’s offshore Khafji oil and gas field, and is still hoping to negotiate a deal to receive a cut in return for contributing to the costs incurred by Saudi Arabia, which shares, and will now operate, the project.

The UAE is expected to see similar growth this year to 2013’s levels, and while some new big projects in real estate and tourism are supportive, these need to be implemented in a manner that avoids the boom and bust cycles seen in the past. For the emirate of Dubai, oil only makes up nine per cent of net revenue and its new 2014 budget featured heavy investment in new infrastructure projects to support its hosting of Expo 2020. The UAE 2014 federal budget aims to stimulate economic growth and boost social services, and increases spending from originally planned levels to AED 46.2bn ($12.6bn).

But despite diversifying more than its Gulf cohorts, the UAE is carrying a large debt load, and is still heavily reliant on oil. State-owned Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (ADNOC) is spending $70bn to hike production capacity above the previous target of 3.5m b/d. It is aiming for a 1m b/d increase to 3.8m b/d over the next decade and seeking to boost production from ageing fields via carbon dioxide re-injection. The IMF puts UAE production at 2.8m b/d in 2013 and natural gas at 1.3m barrels of oil equivalent/day. As part of its drive, Abu Dhabi is revising its concession terms and new players could replace some of its decades-long legacy partnerships with international oil companies.

an OPEC meeting that shale oil would be a ‘welcome addition’ to the

world’s energy reserves and that he was not worried about Iranian oil

bringing about an oversupply. ‘The market will accommodate it,’ he

was quoted as telling an American business news television channel

Capital outlay climbs

Qatar, the richest country in the world with a per capita GDP of $101,200 in 2012, was the fastest growing economy in 2008-12. While this growth will slow it will still remain the highest in the GCC, at five per cent in real terms in 2014, according to IMF projections.

Given that gas makes up a considerable 42 per cent of the country’s GDP, compared to 15.6 per cent for oil, it boasts the second lowest fiscal break-even crude price of the Gulf countries behind Kuwait. But even Qatar’s break-even price has increased as capital spending has climbed. Government outlay on infrastructure spending was to be higher than budgeted for both 2013 and 2014, said Qatar National Bank (QNB) in its latest report. Much of this is in preparation for the country’s hosting of the 2020 World Cup.

Qatar officials appear unruffled by the proliferation of LNG projects elsewhere, which could unseat it as the world’s biggest exporter. They believe that growing demand from emerging markets will mop up production coming on line in 2015 through to 2018 from North American shale deposits, East Africa and Australia. While the rush for US LNG export licenses could affect Qatar’s position in the Asian and European markets, the emirate appears to be taking solace in the slow pace of awards – just five have been given out so far.

Aside from output from the Barzan project, which is targeted at domestic consumption, Qatari gas is unlikely to increase significantly in the near term as there is a moratorium on new export projects until at least the end of 2014 while studies are carried out on the appropriate rate of sustainable extraction from the country’s giant North Field. But once this is lifted, Qatar could rapidly expand LNG production, possibly by around 10 per cent, according to Qatari oil industry officials. Total crude oil, condensates and natural gas liquids (NGL) production in 2012 was around 2.0m b/d, of which 0.7m b/d was crude oil. Qatar produced an average of 726,000 b/d of crude oil in the first 7 months of 2013, down from a peak annual average of 845,000 b/d in 2007. However, in its 2010-14 development plan, state producer Qatar Petroleum budgeted $6.6bn for investment in crude oil projects, and QNB expects crude oil production to rise to an average of 800,000 b/d by 2017.

Meanwhile, Bahrain’s 2013 crude production rate was expected to increase to just over 200,000 b/d with around 52,000 b/d (including condensate) coming from its onshore Awali field, and 150,000 b/d from its portion of the Abu Safa field, which it shares with Saudi Arabia. Bahrain’s share in 2012 was only 127,600 b/d due to maintenance work. The country is aiming to increase Awali’s production to 100,000 b/d by the end of 2020, but this looks ambitious.

Oman’s crude production rate was at an average of 939,000 b/d in the first nine months of 2013, compared to an average rate of 918,500 b/d for full 2012, according to the country’s National Center for Statistics & Information.

Although Oman is a small producer in Gulf terms, its oil revenue nevertheless represents around 75 per cent of the country’s total. For the first nine months of 2013, it was at OR7,904m ($20.5bn), down from the year-ago period’s OR8,111.1m ($21bn) as oil prices edged slightly lower. Gas revenue for the first nine months of 2013 was OR1,090.9m ($2.8bn) compared to 2012’s OR1,224.6m ($3.2bn).

Cash And Trade Magazine For Cash and Trade professionals in the Middle East

Cash And Trade Magazine For Cash and Trade professionals in the Middle East