MENA expansion now has the increased support of export credit agencies. MELANIE LOVATT reports

Export credit agencies (ECAs) have boosted their support for Gulf mega-projects over the last several years. In the wake of the 2008 global financial crisis, they gained importance as sponsors looked to tap more sources of funding. And with deal size on the up, they look set to continue to play a major role in the region’s expansion, particularly in the petrochemical and power sectors.

ECAs are active in classic trade business in the Gulf. For example, in August Air Arabia closed the 12-year financing on its new Airbus A320-200 aircraft using an ECA facility supplied by Germany’s KFW Ipex and covered by Euler Hermes. But big bucks – and in some cases multiples of billions – are also being provided by ECAs via project finance structures.

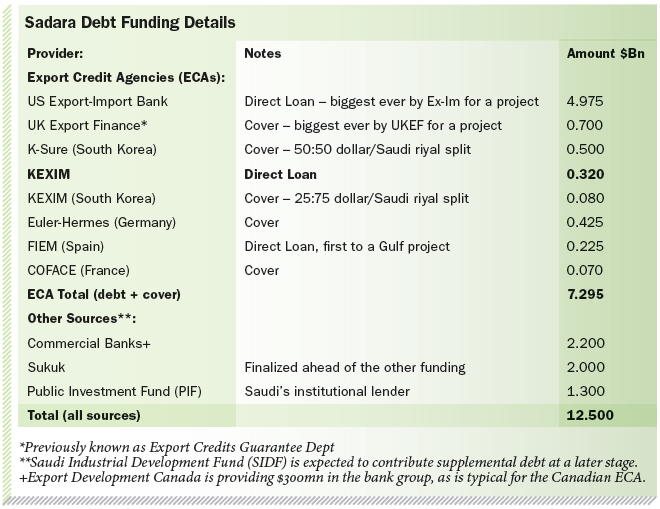

A recent high point for ECAs was Saudi Aramco and Dow’s $20bn Sadara petrochemical project in Jubail, Saudi Arabia. ECA direct loans and guarantees (where banks supply the underlying funding) account for more than 50 per cent of the $12.5bn debt, dwarfing the deal’s $2.2bn commercial bank tranche. ECAs were the first participants in the financing to be approached by the sponsors and their advisers, with the transaction designed to maximise ECA support.

With 26 manufacturing units – making it more of a petrochemical “city” than a facility – it is the Gulf’s largest ever project financing (the biggest, globally, is Ichthys LNG in Australia), and will be the largest project financing to close in the world this year. By mid-2016 at full rates it will produce more than three million metric tons of plastics and specialty chemical products.

Sadara’s sponsors signed the main financing agreements in June with the seven participating ECAs comprising Export-Import Bank of the US (Ex-Im Bank) supplying a huge direct loan of $4.975bn, UK Export Finance (UKEF), previously called the Export Credits Guarantee Department (ECGD), with a $700m guarantee, South Korea’s K-Sure ($500m in cover) and Korea Eximbank ($80m cover and $320m direct loan), Germany’s Euler-Hermes ($425m cover), Export Development Canada with a direct loan of $300m (this sits with the bank funding), France’s Coface with $70m (cover) and Spain’s FIEM providing a $225m direct loan in its first contribution to a Gulf project (see table).

Ex-Im Bank’s Sadara loan, approved by the ECA in September last year, was the largest in its history. The US ECA more than doubled its exposure to the Gulf in fiscal 2012 (ending 30 September 2012) to $15.47bn, versus fiscal 2011’s $7.287bn. It followed this up in April by signing a memorandum of understanding to provide up to $5bn to the Dubai Economic Council.

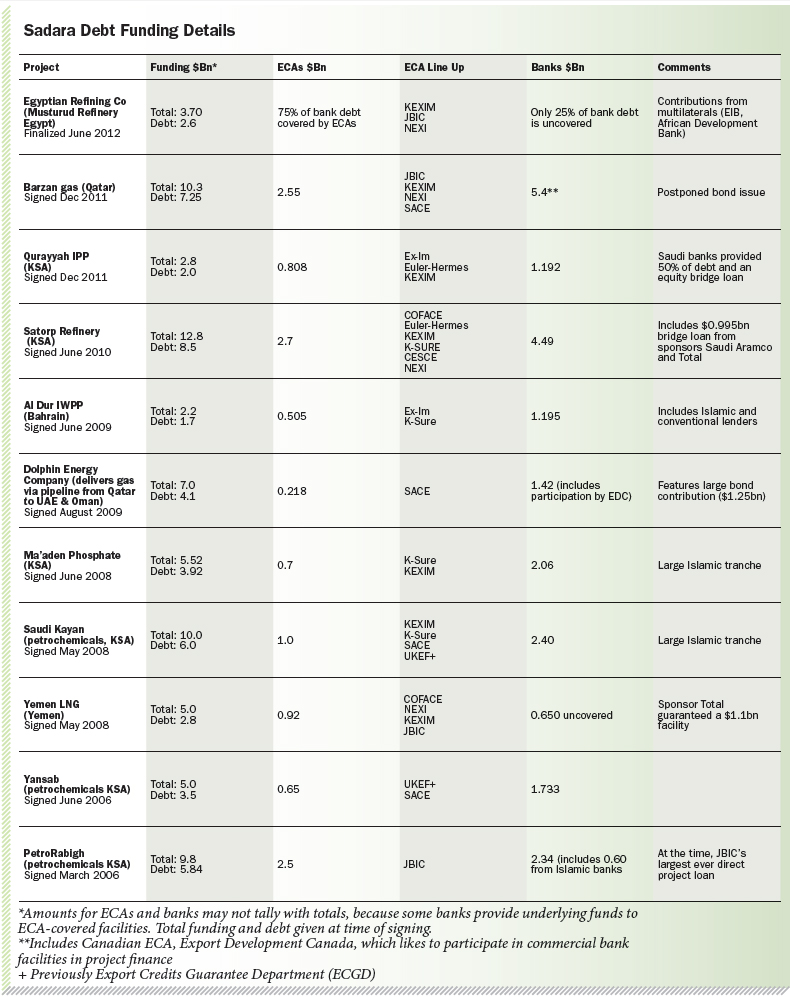

Aimed at supporting procurement of US goods and services by DEC members and customers for infrastructure project, the funds will be deployed across various sectors, including power and water, oil and gas, petrochemicals, ports, railways, and airports. The Korean ECAs, have also stepped up activities in the Gulf, and Japan’s ECA, Japanese Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC), while not present on Sadara, remains one of the biggest lenders to the region (see table).

The perfect storm

A “perfect storm” of events has been behind the uptrend in ECA use in projects, which culminated with the Sadara. Foremost, the scaling up of deals has meant that sponsors need to draw on every available source of funding. A decade ago, a deal sized at a few billion dollars was large, but now deals of $10bn and $20bn are coming to market.

A project finance expert at a European Bank sees this as the key driver for ECA use. “It is fundamental and a function of the increase in project size. To make projects economically competitive, they have to be scaled up and the funding requirements are higher,” she said.

“Without exception, ECAs have heard the call,” she adds. Financial advisers “now petition every conceivable ECA before procurement to see if they can support a project”. Conditions are often “thrashed out with ECAs and if it’s good enough for them, and the multi-lateral lenders, it’s usually good enough for the banks”, she added.

ECAs’ main role is to support their host countries’ exports and government policies, either by providing help with funding, or, as has been more typical, providing guarantees and insuring against risk. But when the global financial crisis sliced into economic growth and cut jobs, ECAs, which are mostly from OECD nations, were urged to ratchet up export support in an effort to improve the trade balance and boost employment for their respective countries.

KEXIM, for example, has established a structuring and financial advisory department to help South Korean companies make their project participation more bankable.

Ex-Im Bank’s chairman and president, Fred Hochberg, said in April that the Sadara transaction will sustain more than 18,000 American jobs across a dozen states. “No other transaction in Ex-Im Bank’s history has supported as many American jobs and no other single transaction has provided so much support to small businesses,” he said.

Of the total loan amount, more than $600m will be used to purchase goods and services from small US businesses. Nurturing SMEs is also taking precedence for governments, given that economic studies show they are a key driver of economic growth.

Prior to the crisis, which hit full force when US investment bank Lehman Brothers collapsed in September 2008, banks had been the biggest lenders to Gulf projects. ECAs were willing Gulf deal participants, but they were often sidelined or confined to minor roles amid fierce bank competition. They were needed outside the oil rich Gulf on what were considered more risky deals, such as those in Egypt or Yemen.

But as the crisis pushed up funding costs, and cut the amount of low margin dollars international banks could supply, ECAs became more important to Gulf sponsors seeking funding for mega-projects.

By and large, domestic conventional and Islamic banks were unable to fill the gaps in the Gulf’s funding requirements. Therefore, ECA participation was more eagerly sought, and sponsor co-lending also became more prevalent. In the wider MENA region, multi-lateral lenders such as the European Investment Bank also saw demand increase.

The toughening of the banking regulatory environment with the ushering in of the Basel III standards has also been a driver in the increased use of ECA funding and guarantees on Gulf projects. That is not to say that banks are no longer important providers of project finance loans – they are.

“The bank model remains key but there are fewer banks able to hold large final takes,” says Andrew Davison, a senior vice president in Moody’s Infrastructure Finance Group. “Any reputable sponsor will look at different funding solutions rather more creatively in the current environment, compared to the previous times when banks could provide best execution,” he explained.

“Banks are concerned about their capital ratios. Long term illiquid assets are a high cost for them to carry with the new Basel regulations,” notes a bank participant on the Sadara financing. Project financings typically have long payback horizons of 15 years, and these can stretch to over two decades for power and water projects.

“For Sadara, ECAs were absolutely crucial given the current debt market conditions. Without them this amount would not have been raised,” he emphasised. Furthermore, he adds that they also played an important role in bringing in some banks, because funding supplied to an ECA guaranteed facility carries a zero risk weighting under the new regulations.

Moving with the times

Over the last several years ECAs have become more flexible in response to changing market conditions, helping to boost their use in projects and other transactions. Many have increased direct lending, as well as continuing to provide more typical ECA services such as cover.

ECAs can also relax requirements for “local content” if they see advantages in supporting certain projects, even if the required loan is beyond the value of the contracts won by their own country.

In the first quarter of this year JBIC and Japanese commercial banks agreed to provide a $3bn loan to state-owned Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (ADNOC). It will be the third $3bn Japanese facility JBIC has arranged since 2007. This move appears aimed at helping Japanese companies secure oil concessions in the emirate, and a continued cementing of the relationship with Abu Dhabi from which it imports almost 25 per cent of its crude, and some liquefied natural gas.

ECAs have also become more accommodating on currency, when needed. On Sadara, K-Sure and KEXIM provided some of their cover in Saudi riyals (the other part is in the more typical US dollar). They have also supported Gulf companies’ efforts to diversify their investor base. For example, state-owned Qatar Petroleum issued a 10-year “Samurai” bond worth Yen 100bn ($1.28bn) in August last year, and this yen-denominated debt was guaranteed by JBIC.

ECAs have also reduced the time it takes to execute deals. “ECAs can – and do – work well together,” said one of the Sadara ECA participants. “There used to be a notion that you couldn’t have more than two ECAs on a project because it would take forever to close,” he said, emphasising that this is no longer the case.

“ECAs are comfortable in partnership not only with each other, but also can form part of multiple pools of funding such as from multilateral financial institutions, commercial banks, capital markets and local markets,” he stated.

Given the number of large deals looming on the horizon in the Gulf, sponsors will continue to tap multiple pools of capital, and heavy use of ECAs will continue.

Following Sadara, the next project in the pipeline for Saudi Aramco and partner Sumitomo is the $7bn expansion of their PetroRabigh petrochemical operation. This is expected to seek funding next year and is likely to use ECAs. The first phase received a $2.5bn overseas investment loan from JBIC. It is likely, however, that Aramco will finance its Jazan 400,000 barrels per day oil refinery via its balance sheet, rather than revert to project finance. The financing for its Yasref 400,000 barrels per day oil refinery, which is a joint venture with Sinopec, is unlikely to require ECAs because the project is nearly complete.

Ma’aden is holding discussions with lenders to fund its $6.5bn phosphates project and ECAs are expected to provide a large chunk of this. Saudi Electricity Company is planning its next independent power project (Dhuba). It has used ECAs for previous deals and is likely to consider them for this project.

Qatar is also likely to tap ECA funds for its planned IWPPs and for the Qatar Petroleum/Shell joint venture that will launch a tender for contractors next year. Abu Dhabi’s nuclear project, Emirates Nuclear Energy Corp, had originally envisaged securing $10bn from KEXIM and $2bn from Ex-Im Bank (which has already been authorised by the US ECA), but recently the emirate has reduced the size of the $20bn debt package for the $30bn project by $5bn, and the ECA component, though expected to remain sizeable, appears to have been scaled down.

These are just a few of the many energy and infrastructure projects across other Gulf countries that will seek to maximise ECA funding.

“In the run-up to the credit crunch, people were asking whether we needed ECAs and multi-laterals, and their role was largely confined to the more difficult countries. When credit quality was hit, we found we do, in fact, need them,” said Liam O’Keeffe, Credit Agricole’s head of project finance and EMEA Loan Distribution. “Without question there is an on-going role for them in the foreseeable future even in developed countries and not just the developing world,” he adds.

Alternative funding pools, such as bonds and Sukuk, are gaining ground, but have yet to take off. Sadara’s $2bn Sukuk offering is the largest seen for a Saudi project, surpassing the $1bn raised in October 2011 for the 400,000 barrels per day Satorp oil refinery project sponsored by Saudi Aramco and French oil major Total. The Sadara Sukuk also notched up another first – unlike Satorp it was finalised ahead of the rest of the funding.

But the Saudi government has been a strong supporter of debt capital market development and gaining traction for the use of Sukuk or bonds for projects outside the Kingdom is proving difficult. Bonds have a number of drawbacks for greenfield projects. Their investors are not typically comfortable with completion risk. During construction, sponsors often need to get “waivers” to the financing agreement to reflect changes to a project, and this would be difficult to accomplish with myriad bond holders. It is easier to push through with an expert group of ECAs and bankers.

Post completion, however, bonds can be used to “take out” bank debt allowing lenders to recycle this capital to other greenfield projects. A recent example is the $825m bond, with an average life of 21.5 years, issued in July for Abu Dhabi’s Shuweihat S2 independent water and power project (IWPP). It is the first tapping of the bond market by an IWPP company in the UAE.

This is a “constructive precedent” said Moody’s Andrew Davison, explaining that it will allow banks to recycle debt, risk capital and shift long-term bank lending to institutional investors. Interestingly, the bond also replaced part of the JBIC facility as well as the bank debt and sponsor subordinated debt. “There is a greater incentive to refinance banks rather than ECAs,” he said.

However, the “take out” option will have to gain ground to allow banks to churn enough funding to step up lending to greenfield projects. Thus, for the foreseeable future, ECAs are expected to remain significant players on Gulf mega-projects. In the wider MENA region, they will eventually be needed to mitigate risk for Arab Spring country projects, especially for Egypt, and, ultimately, Iraq’s energy and infrastructure funding needs could present further opportunities.

Cash And Trade Magazine For Cash and Trade professionals in the Middle East

Cash And Trade Magazine For Cash and Trade professionals in the Middle East