Islamic finance is one of the world’s fastest-growing asset classes. However, a number of barriers are currently preventing the sector reaching its full potential – particularly the lack of a uniform set of rules and regulations for Sharia

financial institutions at Commerzbank

compliance, says CARSTEN KAYATZ, senior product manager for financial institutions at Commerzbank

Contemporary Islamic banking has its origins in Egypt. The first mutual savings bank following interest free principles was established there in 1963 with German support. Currently, there are around 500 Islamic banks, providing services across 75 countries, whose Sharia-compliant banking and finance assets now total approximately US$1 trillion.

The most recent economic forecasts continue to point towards sustained, rapid growth – industry estimates suggest this expansion could total up to $5 trillion in Sharia-compliant assets by 2016.

This expansion brings with it opportunities for Islamic and non-Islamic corporates and financial institutions alike. In their efforts to gain access to the necessary capital and liquidity to meet the growing demand of their clients, Islamic banks need to be able to access funding (from banks and the global capital markets) in a manner that is compliant with Islamic law, in particular the prohibitions on charging interest and trading debt.

To date, there has been a clear lack of Sharia-compliant instruments meeting today’s needs to manage short-term liquidity. Likewise, for non-Islamic companies seeking to work with financial institutions in the Islamic world, Islamic finance provides a means to access a rapidly expanding source of capital.

However, Islamic finance has yet to become fully established alongside conventional global banking instruments. In order to become more widely utilised internationally there are a number of challenges the sector needs to overcome – particularly in adopting a more standardised financial infrastructure.

Overcoming these complexities successfully is often difficult for those with a predominantly regional focus on Islamic financial institutions and a moderate international presence. Conversely, operating successfully in this environment as a non-Islamic bank requires both a high international profile, and an established footprint in both Islamic and conventional business areas, alongside experience in providing non-Sharia-sensitive as well as Sharia-compliant cross-border services.

The necessity for knowledge

Based on Islamic (Sharia) law, Islamic banking aims to be socially and ethically responsible, and embraces high transparency and shared risk. Core features of the law as it pertains to finance include the prohibition of interest, speculation, gambling, and investment in products such as alcohol and pork (just to give a few examples).

Additionally, money is regarded as just a medium of exchange and has no intrinsic value – ie, it can’t be utilised to generate income in itself and trading in debt is prohibited.

Instead, Islamic finance utilises a number of distinct products and services. Of these the primary kinds are Murabaha – a kind of Islamic loan involving the selling and buying of an asset – and Sukuk – effectively, a Sharia-compliant form of bond.

Murabahas (selling and buying transactions) are by far the most popular Islamic products available, accounting for a majority of the total Islamic finance market. When entering Islamic markets, one should primarily be aware of what types of underlying assets are admissible. Sharia law forbids this from being gold or silver (considered as substitute money), so a different precious commodity, such as platinum or palladium, is usually purchased instead.

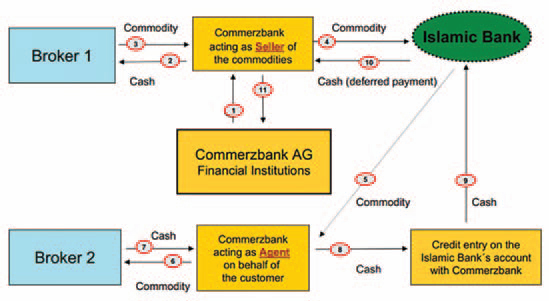

A Reverse Murabaha (Tawarruq) facilitates Sharia-compliant funding for clients requiring liquidity to be advanced. When conducting a Murabaha, the bank (say, Commerzbank), acting as a supplier and in agreement with its Islamic client, purchases a commodity from a broker (see stages 2-3 on the above chart).

This commodity is then purchased by the Islamic bank (stage 4), which agrees to pay Commerzbank for the commodity the purchase price (cost plus an agreed margin), on deferred terms (usually 60, 90, or 120 days). The Islamic bank then immediately asks Commerzbank to sell the commodity on their behalf (stage 5). Acting in its role as agent, Commerzbank then sells this commodity on to a willing broker (stages 6,7), and transfers the money raised to the client. Finally (stages 10-11), the Islamic bank completes payment to Commerzbank for the commodity originally sold to the Islamic bank (at stage 4 on the chart).

In this manner, the client is able to raise liquidity without breaking the religious prescriptions in trading in debt or charging interest.

Need for international framework

However, a fundamental impediment to the efficiency of these kind of transactions is created by the complex web of legal requirements needed to ensure Sharia compliance.

Islamic banking transactions have to follow Islamic rules, as well as being subject to secular national laws (these laws can differ widely on a country-by-country basis). However, there is no generally binding, international law regulating Islamic banking transactions. Instead, different Islamic schools of thought generate different interpretations of Sharia compliance, and demand different legal requirements.

A Sharia-compliant governance framework for the global Islamic finance industry is needed as much as a central regulator (if necessary, in each Muslim country) in order to set rules of Sharia governance in the respective countries’ jurisdictions. This framework and its master documentation should be backed by one single Sharia board authority, removing the need for the reiterative submission of documents to individual Sharia boards.

Some of the leading Sharia advisers claim manifold opinions lead to more financing options. However, the question is whether more options are necessary given there are already Sharia-approved daily financial transactions and, to counter another scholar’s argument, whether diversity is a development impetus towards the expansion of Islamic banking.

As a further complication, non-Islamic corporations dealing in Sharia-compliant products and services, such as Commerzbank, must also ensure that their contracts are valid and enforceable within their own jurisdictions.

All contracts concluded by Commerzbank with Islamic international banks are required to be governed by English law. This is necessary because the Islamic principles and jurisprudence that constitute Sharia law derive from a number of sources, are subject to varying interpretations, and do not, therefore, represent a codified system of law.

Whether a planned transaction or contract is in accordance with the national secular law is decided by Commerzbank’s legal department, often in conjunction with specialist law firms in the relevant countries.

However, whether the transaction is in accordance with Sharia law is the decision of the client’s own Sharia-Board – and decisions between boards often vary. Nevertheless, these supervisory boards constitute a crucial role in Islamic finance and are, therefore, a leverage towards a stable, well functioning and ideally efficient Islamic banking market.

Satisfying these various sets of conditions requires experience, flexibility, and the ability to build and maintain long-lasting relationships. Over the course of its 140-year-history Commerzbank has a strong record of engagement with international business (44 of its 60 locations worldwide are dedicated to financial institutions business), and has been involved in Islamic markets for a number of decades.

The evolving requirements of Islamic clients, driven by continued economic growth in the sector, has necessitated international banks’ service offering moving in step with the demand for a more all-inclusive range of Sharia-compliant products and services, including payroll management and fund-raising transactions.

In turn, this has required an on-the-ground presence – Commerzbank has been represented in the Gulf area for 35 years, and for many years in other Muslim countries – and made experience of the sector and knowledge of clients even more vital in order to develop products that mitigate the difficulties arising from a lack of standardised regulations for Islamic banking.

The key to servicing clients

Indeed, developing a standardised set of rules and regulations for Sharia-compliant banking is proving a difficult challenge. Alongside different religious interpretations, and the proclivities of individual clients, the various standard boards, the AAOIFI (Accounting and Auditing Organisation for Islamic Financial Institutions), IIFM (International Islamic Financial Markets) and IFSB (Islamic Financial Services Board), to name only three of them, are to a certain extent competing organisations. As a result, their rules do not tend to function as standards but only as recommendations, although the Malaysia-based IFSB has at least introduced standards on Sharia governance for local financial institutions.

Given the impediments, gaining universal acceptance of all the current rules and products is probably unrealistic. Instead, it is, perhaps, more realistic, at least in the short-medium term, for non-Islamic banks to focus on innovating generic products that can subsequently be customised to meet the particular Sharia demands of customers in different jurisdictions. The recently announced Islamic Interbank Benchmark Rate (IIBR) for pricing Islamic instruments – even showing similarities with conventional interest rates – might be a useful step towards standardisation.

Building a global future

Even with these innovations, in order to go truly international, the mind-set of the practitioners and supervisors of Islamic finance must change. Currently, the tendency is towards focusing on the differences in views. The result is a changeable and opaque regulatory environment that generates inefficiencies and creates higher barriers of entry to Islamic and non-Islamic institutions alike.

Instead, in order to promote the global growth of the Islamic finance sector, it is important that interested parties concentrate on seeking out the similarities and common denominators between the various competing interpretations of Islamic law. In this respect, organisations such as IFSB, AAOIFI and IIFM have provided a useful first step by drawing up initial frameworks and guidelines. Hopefully, these will be built on, rather than used as ends in themselves.

Failure to overcome these challenges could severely curtail the Islamic financial sector’s potential for growth. There is growing concern that if these differences remain unresolved, Islamic finance could never become popular, even among Muslims.

Despite these difficulties, there is optimism that they will be overcome and that Islamic capital markets will increase in the future and will become a source of funding for corporate, governmental and public sectors the world over. n

The author, Carsten Kayatz is senior product manager for financial institutions at Commerzbank, a role he has held since 2008. Previously, he was regional manager, financial institutions, responsible for Mexico, Central America, Caribbean, Venezuela, Colombia and Ecuador. Having joined Commerzbank in 1987, Kayatz has also worked as the chief representative for Commerzbank Rio de Serviços, Brazil, as well as assistant vice-president, Middle and Eastern Europe, Iberian Peninsula and Maghreb countries. Before that, he was for a period the bank’s relationship manager for Spain, Portugal and North Africa. He studied law at the University of Bonn, before undertaking additional studies at the University for Management Sciences in Speyer.

Cash And Trade Magazine For Cash and Trade professionals in the Middle East

Cash And Trade Magazine For Cash and Trade professionals in the Middle East