BARBARA S. ISMAIL, executive vice-president, Cash Management Matters, looks at the argument that says financial stringency as a cure for economic weakness may be the wrong action at the wrong time

BARBARA S. ISMAIL, executive vice-president, Cash Management Matters, looks at the argument that says financial stringency as a cure for economic weakness may be the wrong action at the wrong time

Common wisdom, as promulgated by the IMF and other supranational organizations, has been that austerity is the best medicine for ailing economies, and countries from Argentina to Thailand have been treated with mega doses when they’ve come to those agencies for assistance.

A well-quoted article by Harvard economists purported to quantify the effect of economic profligacy on shrinking economies, describing a “tipping point” where government debt inevitably led to stalled or negative growth. On the surface, this appeared to prove the case for austerity, justifying the decades-long insistence on prescribing such a regime to suffering countries throughout the globe.

The World Business Outlook, published in April of this year by the International Monetary Fund, commented:

once commented that struggling

European countries could run

their economies with the precepts

of a good Swabian housewife

“Much of the empirical work on debt overhangs seeks to identify the ‘overhang threshold’ beyond which the correlation between debt and growth becomes negative. The results are broadly similar: above a threshold of about 95 per cent of GDP, a 10 per cent increase in the ratio of debt to GDP is identified with a decline in annual growth of about 0.15 to 0.20 per cent per year.”

However, a recent rebuttal by professors and graduate students at the University of Massachusetts looked more closely into the results and methodology behind the paper, and found mistakes that seem to call the underlying thesis into question.

Reinhart and Rogoff, the authors of the original study Growth in a Time of Debt, published in 2010, have strenuously defended their results, even while conceding the Excel spreadsheet in which they interpreted their raw data contained coding errors.

The debate on the paper, leading directly into a wider debate on the efficacy of austerity budgets in increasing economic activity has taken place in the Op-Ed columns of the New York Times. Reinhart and Rogoff continued to claim “growth is about one percentage point lower when debt is 90 per cent or more of gross domestic product”: this is one of the primary conclusions of their paper.

Pollin and Ash, the academics who refuted this together with Herndon, commented in the New York Times (4/26/13):

Reserve Bank, is an advocate of the theory

that a lack of credit was one of the primary

causes of the Great Depression continuing

for as long as it did

“There are serious problems with this claim. The most obvious is that the median growth figures they reported in the 2010 paper are distorted by the same coding error and partial exclusion of data from Australia, Canada and New Zealand that tainted their average growth figures. When we corrected for these errors, the difference in median economic growth rates was only 0.4 percentage points between countries whose public-debt-to-GDP. ratio was between 60 per cent and 90 per cent, and those where the ratio was over 90 per cent (2.9 per cent median growth versus 2.5 per cent). The difference between 0.4 per cent and 1 per cent is quite substantial when we’re talking about national economic growth.”

Furthermore, adjusted data post 2000 reveals little if any drop in economic contraction when public debit exceeds the 90 per cent threshold. It may also be useful to note that some of the largest falls in economic activity in recent years, in the United States, Spain and Ireland, for example, were presaged by debt build up in the private financial sector, not public; and in Iceland, where the government refused to take on private bank debt (as opposed to Ireland, which did, and the United States’ Wall Street bailout) the economy recovered relatively quickly.

Paul Krugman, a Nobel Prize winning economist, Professor at Princeton University and columnist on economic matters for the New York Times has long been an advocate of increased government spending in the face of the depression/recession and high unemployment that hit the United States in the wake of the Lehman Brothers’ collapse and the bursting of the housing bubble.

Without consumer spending to encourage the economy, he argues, government becomes the spender of last resort. The sharp downturn of 2008 left consumers unable or unwilling (or both!) to spend, and as economic activity contracted, unemployment exploded, and even now remains high.

Krugman insists it is unemployment that is the greatest danger to the economy, not government spending, which should be encouraged in situations like this rather than reined in.

In this, he stands diametrically opposed to more conservative politicians in both the West and supranational agencies. Classically, the IMF (and other agencies like it) would insist on strict austerity from countries that had approached it for aid. This included slashed government budgets, tight spending regimes and, similarly, Spartan currency policies.

These policies are undertaken in the belief that a decrease in government spending with a concomitant decrease in government deficits will institute a virtuous circle in which national economies will live within their means and thereby grow in a safe and sustainable manner, avoiding the policies that led them to the IMF in the first place.

In this paradigm, the economy of a nation or even an economic zone (eg, the Eurozone) is likened to a household writ large, made clear in Chancellor Angela Merkel’s comment that struggling European countries could run their economies with the precepts of a good Swabian housewife.

As Krugman has repeatedly counselled, a national or international economy requires far more give and take: one country’s spending is another one’s earning, and all cannot export their way out of trouble at the same time.

When consumer spending skids to a halt, domestic sales plummet, with knock-on effects to manufacturing and agriculture. In situations such as these, private financial institutions may also pull back, reluctant to lend, and the lack of readily available credit only exacerbates the existing downturn, which happened in the Great Depression of the 1930s and again in 2008.

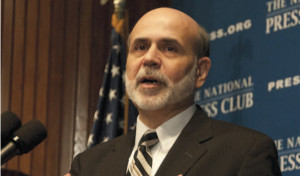

Ben Bernancke, Chairman of the U.S. Federal Reserve Bank, is a scholar of the causes and effects of the Great Depression, and an advocate of the theory that a lack of credit was one of the primary causes of the Depression continuing for as long as it did, and his belief has certainly informed his policy of keeping US interest rates at historic lows in order to stimulate economic activity.

Krugman, too, has stated that insufficient credit activity on the part of banks now fearful of the lending that almost toppled them (thereby swinging the pendulum from undertaking almost no credit checking in the case of sub-prime mortgages to the current situation in which even qualified borrowers can often not find funds) combined with tepid government spending (at a time when economic activity must be stimulated rather than curbed) has kept the US in a recession, or at least out of a robust recovery, far longer than necessary.

This policy has been followed with even more enthusiasm in Europe, where the economy remains even more deeply mired in high unemployment and low (or negative) growth, to the point where unemployment actually threatens the social order.

The firm adherence to austerity as a cure for economic slowdown appears, Krugman argues, as a moral decision: a troubled country plagued by over borrowing must curb its appetite for funds and “learn” to live within its means. The fact that the private sector rather than the public may be responsible for the debt has made little difference in the insistence on cutting spending either in the developing world or in Europe.

The current debate regarding Reinhart and Rogoff’s paper is not a merely academic one, but rather an argument with practical consequences for the real world. For if large government debt does not necessarily slow down an economy, and if government debt overhang has different consequences than private or individual indebtedness, then insisting on austerity as a cure for economic weakness may be the wrong action at the wrong time.

Cash And Trade Magazine For Cash and Trade professionals in the Middle East

Cash And Trade Magazine For Cash and Trade professionals in the Middle East

One comment