One of the greatest duelling pairs in the history of crime fiction were the cerebral detective Sherlock Holmes and his nemesis Professor Moriarty. And, in spirit as it were, they might be living on in the digital age as Good and Bad clash for supremacy in the field of cybercrime in the financial services sector. What guards and tripwires can banks and corporations (playing the part of Holmes) put in place to foil the wiles of the cyber-Moriarties of the future? MADHU K, chief information security officer, Polaris Consulting & Services Ltd, dons his deerstalker and goes in hot pursuit of an answer.

One of the greatest duelling pairs in the history of crime fiction were the cerebral detective Sherlock Holmes and his nemesis Professor Moriarty. And, in spirit as it were, they might be living on in the digital age as Good and Bad clash for supremacy in the field of cybercrime in the financial services sector. What guards and tripwires can banks and corporations (playing the part of Holmes) put in place to foil the wiles of the cyber-Moriarties of the future? MADHU K, chief information security officer, Polaris Consulting & Services Ltd, dons his deerstalker and goes in hot pursuit of an answer.

There is nothing intrinsically mysterious about cyber (or computer) crime. It is simply crime involving a computer and a network. Of course, significant technical expertise is required to understand certain types of cybercrime, but everyone can – and should – recognise the primary forms and perpetrators.

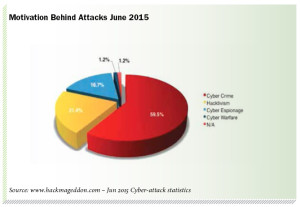

Just as in the world of “offline” crime, means and motivations vary. Many of the nameless faces behind organised cybercrime, now estimated to be worth US$300bn a year, are in it for monetary gain and exploit jurisdictions lacking the proper legal frameworks or technical capabilities to fight such attacks.

Those engaged in cyber-espionage steal information to sell to third parties, whereas “hacktivists” are usually more interested in data breaches and exposing the secrets of organisations or governments. Those with political or ideological motivations may compromise an organisation’s information or systems to achieve their goals. And possibly the most insidious threat of all comes from within, from malicious – or even accidental – acts by a company’s own employees.

Targeted crime

According to a recent report by cybersecurity specialists Raytheon1, the financial services sector:

- Encounters security incidents 300 per cent more frequently than other industries

- Is the target of 33 per cent of all “lure stage” attacks

- Ranks third for targeted “typosquatting”

- and – if we look at banks specifically – is the primary target for credential stealing.

Furthermore, these attacks can wreak huge damage. Moscow-based security firm Kaspersky Lab recently reported that a gang of international hackers had installed malware allowing them to take control of banks’ internal operations and steal as much as $1bn from 100 banks across 30 countries before being detected. Wait, read that again – not “stopped”, merely “detected”!

With the era of digitisation, electronic platforms and mobile banking upon us, the issue of cybercrime is only going to increase. Furthermore, away from trade and transaction concerns, all customer-facing businesses are now learning to leverage social media to better connect with their customers – opening up even more avenues of attack for cybercriminals. A case for Holmes indeed…

So where to start? The first step lies in understanding the tools of the trade. But the sheer pace of technological innovation means cybercrime – like banking security – is rapidly and continually being upgraded, making it impossible to say with certainty which methods of today will still be around tomorrow.

Currently, some of the most common threats include botnets; networks of software robots that automatically spread malware, often moving data (via “fast flux”) between computers so quickly that it is hard to trace its source. Another method is the corporate account takeover, where cybercriminals covertly obtain a company’s banking credentials and use software to hijack a computer remotely to steal funds.

A perennially present threat is social engineering (including more familiar phishing), which affects both consumers and employees and exploits human gullibility using lies and manipulation to trick people into revealing personal or sensitive information.

Common sense coupled with effective safe-guards should suffice to stop users falling victim to some of the oldest tricks in the book – even Sherlock Holmes’ faithful but not-so-bright companion Dr Watson would know to be wary of emails from “a Nigerian prince” – but such crime continues, and is all the more abhorrent for intentionally targeting the vulnerable.

on the keyboard?

Bolstering security

Of course, banks are fully aware of all these threats and have made strenuous efforts to combat cybercrime at both policy and administrative level, and through the deployment of sophisticated technological controls. However, there is a more fundamental structural imbalance between banks and cybercriminals that banks will need to address if they are to win this war.

For cybercriminals, specialist knowledge and the latest technology form the life-blood of their business, and are the focus of constant innovation.

But for financial service organisations, security – the barrier that needs to evolve just as quickly as this innovation – risks being perceived as yet another cost, and, therefore, is not always the recipient of sufficient attention nor investment.

While cybercriminals are highly proactive in seeking out bank vulnerabilities, banks on the whole are – due to the nature of their highly regulated industry and fiduciary responsibilities – restricted to playing a more reactive role, only adapting when required to by regulatory, legal or contractual obligations, or in response to specific identified threats.

Most banks have detailed incident response plans, yet cost constraints can sometimes mean that even these are insufficiently tested, resulting in delays in case of a real incident. This is not to say banks are unaware or underestimating these threats; merely that the traditionally slow-moving industry struggles to keep up with its more nimble foes, who operate far outside of regulatory restrictions.

Finally, cybercriminals will often share knowledge with each other, whereas banks – wary of losing customer confidence or revealing internal weaknesses in today’s highly competitive environment – will often avoid sharing information on cybercrime, or disclosing more than they are required to on data breaches.

What all this adds up to is that even as banks adopt more advanced technological controls and procedural measures to prevent cyber-attacks, cyber-Moriarty is both fast and flexible, and will always be a step or two ahead – making it impossible for banks ever to eradicate cybercrime completely.

The threat from within

If this picture weren’t already bleak enough, banks must also contend with internal risk. Their zettabytes and yottabytes of data are stored in what are ultimately insecure systems – as no system has yet been built that cannot be hacked.

If this picture weren’t already bleak enough, banks must also contend with internal risk. Their zettabytes and yottabytes of data are stored in what are ultimately insecure systems – as no system has yet been built that cannot be hacked.

Such vulnerability will only increase in line with the growth of online payment systems, and today’s expectations for “anywhere, anytime, anyhow” payments, via computers, mobiles, tablets and “smart” watches. Banks of all sizes are incorporating mobile banking as a regular delivery channel, and implementing strategies around social media; admirable developments that will nonetheless be viewed by cyber-Moriarty as rich pickings.

As more money floods the web in new and evolving formats, cybercriminals will be quick to exploit as-yet-unknown points of weakness. Likewise, the growing use of social media risks making huge quantities of personal and sensitive information easily available to hackers and provides easy prey for organised crime.

One major challenge in today’s BYOD (Bring Your Own Device) culture is the use of personally-owned (and, therefore, unsecured) smartphones, laptops and tablet computers, together with the apps and adware these devices come with.

Such devices have opened up an entire new universe of cybercrime opportunities – “BYOD” might as well be dubbed “bring your own disaster”. As the future brings more apps, more types of device and greater (often automated) interactivity between devices, the threats posed will increase exponentially. Indeed, many employees may not even be aware of their devices’ security and privacy settings, and will frequently change or upgrade devices without fully clearing data. Furthermore, intense market pressure on time-to-market in the phone industry in particular means providers may be tempted to push out new operating systems and phones that lack adequate security features.

App stores may have strict guidelines for developers and ad posters, yet security measures are not among them. Android mobile devices combine supposedly-private personal data, photos and owner location with sensitive business information, contacts and intellectual property. Additionally, downloaded apps – and their use – can threaten all information on a device. These can include malicious apps stealing information once installed, legitimate apps written insecurely by developers, legitimate apps using insecure but aggressive ad libraries, malware/aggressive adware that passes Google Play checks and is thus assumed safe, identity theft, and premium rate phone and SMS fraud.

Add to this the possibility of underlying social and socio-political unrest in the (widely mistaken) belief that the increasing digitalisation of society brings about a reduction in employment opportunities, and you have a new recruiting ground for all kinds of cybercriminal. Finally, let’s not forget that the proliferation of technology means your classic disgruntled employee has an immense amount of sensitive company data at his fingertips, and the power to share or wield it at a moment’s notice. No longer is it a simple case of putting his personal effects into a cardboard box, and sending him on his way.

Every Holmes needs a Watson

Having painted such a dystopian picture of a future wracked by cybercrime, how can the likes of a Sherlock Holmes protect our data, money and commercial flows? The answer lies neither in silver bullets nor late-night stalk-outs, but in a clear holistic strategy, a much more proactive approach, and the understanding that the creation of partnerships – just like that of Holmes and Watson – is critical if Moriarty is to be defeated.

First and foremost, banks must address their traditionally “siloed” mentality. Many vital functions such as intrusion detection, security information and event management (SIEM), identity and access management, data loss prevention (DLP) and incident management continue to be treated as separate areas, when a holistic approach would be far more effective in the battle against cybercrime. Banks must evaluate how the controls already available to them can be integrated into an enterprise-level security framework to protect the organisation’s information and assets more ably.

On the human front, a holistic approach means ensuring there is enterprise-wide awareness of the seriousness of cyber-threats, and the need for enforcement of controls amongst all stakeholders – including employees, contractors and business partners. It requires an information-centric approach to identifying and classifying confidential and sensitive data – where it resides, who has access to it, how it enters and leaves an organisation. And access to data must be provided entirely on a need-to-have and need-to-know basis, and access to information on personal devices should be strictly limited.

In any vision of a crime-free future, operating systems and devices (laptops, tablets, etc, including BYODs) will be standardised (i.e. prescribed) within an organisation, ensuring all systems have up-to-date antivirus protection and the latest software patches at all times, and with detailed data logs in place. All employees will be clearly instructed on social media boundaries to avoid unwanted entry points.

A company’s network will be secured with a virtual private network (VPN), to which employees and business partners connect through a virtual private server (VPS), rather than via the internet. Online services and critical applications will come with multi-factor authentication and have one-time-passwords (OTPs) sent to the user’s phone, in addition to the customary username and password.

Biometrics may also be added as authentication methods, enabled by smartphone and tablet fingerprint readers and high-resolution cameras, and could be bolstered by speech or facial recognition.

In terms of internal infrastructure, banks and corporations alike should review their IT architecture, and:

- Integrate technological controls such as encryption, SIEM and DLP

- Encrypt data both at rest and in transit

- Monitor data and workflows

- Analyse the security of all systems and locations that receive or send data

- Implement end-point controls

- Monitor payment file activity transmission status

- and manage digital key token assignments such as SWIFT’s new single, multi-network digital identity solution.

All inbound and outbound traffic should be routinely logged, with thresholds set in for abnormal spikes to trigger alarms. Banks must also conduct real-time analysis of security alerts generated by network hardware and applications. These tasks will be made easier by combining physical access logs with logical access logs; both will be required if employee access is to be authorised, making it that much harder for cybercriminals to get their foot in the door.

Proper Failure Mode Effect Analyses (FMEA) will identify typical failure points and check whether adequate controls are in place to detect and provide the required alarms. Finally, across-the-board security intelligence will be gathered and used proactively to anticipate future threats.

As is often the case when reality replaces what is (as yet) fantasy, the future of cybercrime-fighting is seen as being less glamorous, and, ultimately, comes down to details. As Holmes himself once said, “The little details are by far the most important.”

Joining the force for good

A cybercrime-free world, where our bankers have been victorious, would also have one slightly more radical change, and a scenario that may seem unlikely at present.

Rather than fighting, one by one, the pervasive and shape-shifting Moriarty, imagine if banks, regulators, innovators and other key industry players – all our forces for good – came together over dinner to compare notes, without fear of competition or ridicule.

In no time at all, they would detect patterns, predict the next moves of Moriarty and his henchman, and help each other to innovate, strategise, and implement the tricks and tripwires necessary to prevent cybercrime.

At present, many banks and financial institutions prefer to suffer cyberattacks in silence – yet industry-wide dialogue, to share experiences and create new solutions, would bring benefits that are currently unobtainable to any bank alone.

Last but not least, banks, corporations and end-customers alike must understand that the threat is real. Corporations and consumers should heighten their expectations when it comes to privacy and security, and banks in turn – in their core responsibility as guardians of the real economy – must make cybersecurity a definite priority.

Leave it too late, and Moriarty is sure to pounce.

Cash And Trade Magazine For Cash and Trade professionals in the Middle East

Cash And Trade Magazine For Cash and Trade professionals in the Middle East