ALEXANDER R. MALAKET, president of OPUS Advisory Services International Inc., looks at the evolution of the ‘relationship and trust theme’ from concept to business practice and operation. In other words, from ‘discussion to action’

ALEXANDER R. MALAKET, president of OPUS Advisory Services International Inc., looks at the evolution of the ‘relationship and trust theme’ from concept to business practice and operation. In other words, from ‘discussion to action’

There has been a great deal of focus, particularly since the eruption of the financial crisis, on the importance of a trust and relationship-based approach to banking, including trade and transaction banking.

Trade and supply chain finance given their cross-border nature, already rely to a significant extent, on an underlying desire between buyer and seller to conduct business, and have evolved several features, particularly in traditional instruments such as documentary letters of credit, to assist in managing risk issues and to facilitate the development of trust through successful transactions.

The MENA region is shaped by high-context cultures in which relationships, trust and a handshake are fundamental to the conduct of business, and where, market observers will note, the banks have remained largely focused on fundamentals.

Students of intercultural effectiveness will suggest that the relationship dimensions are often more important than a contract, that communications are fundamentally about the development of relationships, and where disagreements are resolved on the basis of the relationship and its long-term direction.

Students of intercultural effectiveness will suggest that the relationship dimensions are often more important than a contract, that communications are fundamentally about the development of relationships, and where disagreements are resolved on the basis of the relationship and its long-term direction.

Low-context cultures focus on an exchange of information and data, and contractual parameters may have more influence over commerce than the relationship dimension.

The business of trade, between an importer and an exporter, or between a buyer and a community of suppliers, relies on relationships – and ideally, trust, to manage the conduct of business. Documentary credits, for all their flexibility and effectiveness, and for all the advances in process and technology, still exhibit high rates of non-compliance of documents upon first presentation, in some Nordic markets reportedly as high as 80 per cent.

The resolution of such discrepancies, which allow for the ultimate conduct of trade, often comes down to good-faith collaboration and negotiation based on relationships – in turn, helping importers and exporters to develop trust.

The discussion of trust may be new – or renewed – in some parts of banking and finance. However, it is entirely familiar, and fundamental to the business of international commerce, and to the finance of international trade. This, combined with the long-established, relationship-based commercial practices in the MENA region, sets a solid foundation for the evolution of the “relationship and trust” theme, from concept to business practice and operation: from discussion to action.

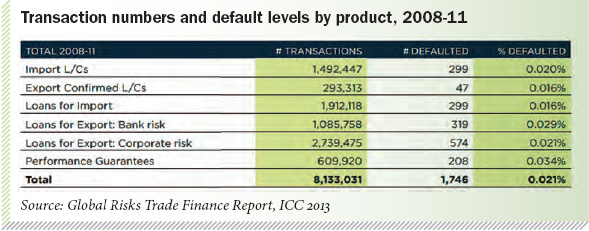

Trade financiers have a unique opportunity coming out of the crisis to articulate the value proposition of this business in support of international commerce, demonstrating to clients the characteristics of trade finance in terms of negligible default and loss rates, which have now been documented through the ADB/ICC Default Register.

The level of default (a significant percentage of which is, in the end, resolved and recovered) lends credence to the assertion of trade financiers that traditional trade finance mechanisms are effectively risk-mitigated and consistently contribute to the successful conclusion of transactions, even in the most challenging markets or commercial contexts.

Beyond that, the existence of well-established rules and practices, such as the Uniform Customs and Practice for Documentary Credits, or UCP, which has been in effect since 1933, provides a transactional level of comfort, in that the International Chamber of Commerce acts as a trusted interlocutor in the interpretation and application of those rules globally – with such effectiveness, that the UCP (and others with similar sets of rules) have been recognised and integrated into various legal traditions.

A similar approach has been employed in the development, market acceptance and current dissemination of a set of rules related to the Bank Payment Obligation – a new instrument of trade finance developed by SWIFT and the ICC.

In addition to a degree of legal robustness, the rules governing the use of traditional instruments of trade finance rely heavily on relationships and some level of trust between financial institutions engaging in the financing of trade flows.

There are, admittedly, financial institutions and corporates that take a far more competitive and less collaborative approach to the conduct of trade, whose specialists will seek opportunities to take advantage of any loopholes in the rules or related processes. Some will engage in outright abuse of the framework around trade and trade finance, but the majority of bankers and corporates appear more interested in the successful completion of transactions and the development of longer-term relationships.

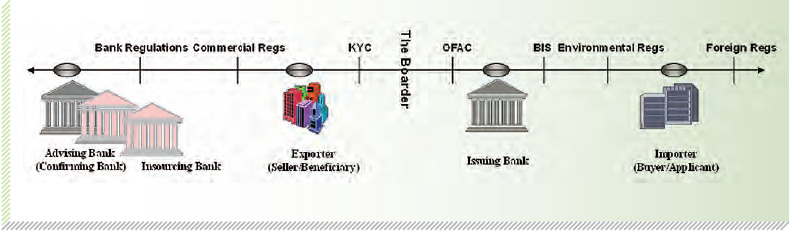

In this context, the relationship and trust discussion around trade finance shift quickly from theory and concept, to transactional and operational reality. Additionally, certain political objectives arising from the global crisis, such as the imperative to engage in greater regulation of the financial sector, contribute to the dynamics around banking, trust and trade.

Some bankers object quietly to the “regulatory and compliance empires” evolving within their institutions – and ruefully note that they now spend more time responding to the demands of regulators than they do to the needs of their clients. It is difficult to find a sympathetic audience for such concerns in many markets at the moment, given the role of banks in precipitating the global crisis. However, trade financiers – far removed from the triggers of this crisis – have both a right and an obligation to advocate in favour of this business that facilitates 80-90 per cent of global trade flows.

Trade financiers may have an opportunity to incorporate their response to regulatory and compliance requirements – such as evolving anti-moneylaundering measures and KYCC (“Know your Customer’s Customer”) requirements – into a relationship and trust discussion with clients.

Investment advisors and bankers have long been required to undertake due diligence relative to their own clients (KYC), however, more recently, regulators have demanded a standard of due diligence that extends to the business partners and counterparties of a bank’s client.

In the trade business, this may require a financier to complete due diligence on a local client and on a buyer or supplier in a remote market across the globe, where commercial information – such as credit reports and financial statements – may be difficult to access, or simply not available.

Trade banks that, nonetheless, succeed in devising processes, or developing networks to undertake appropriate due diligence, can demonstrate an ability to help businesses with some level of due diligence on potential partners, contributing thereby to the development of the initial foundation of a relationship.

The regulatory requirements around banking, and particularly international banking, are likely to continue to increase over the coming several years, even in markets where banking practice has been sound, and adverse economic impact has not been in evidence, simply as a result of the interdependence of financial sectors globally.

A useful perspective on the current regulatory reality might be to redefine the conversation around regulation, from a commercial burden to a relationship opportunity, and to leverage the data collected in the context of regulatory compliance activities to help inform the relationship efforts of trade financiers.

A consistent reality in trade banking is a tendency among banks, even top-tier institutions, to underestimate and underleverage their operations units; in this respect, the relationship and trust discussion can and should shift beyond front-line sales specialists to include operations specialists as a means of mining data and relationship insight that can come only from daily interaction and transaction-level involvement with a client’s business.

At the same time, promoting a dialogue with customers that involves multiple levels of a trade business will reinforce the relationship and trust message and will naturally take this from a theoretical discussion to a transactional reality.

A regulatory requirement as esoteric as the Basel II and III capital adequacy rules can also serve as a basis for enhancing the trust and relationship dialogue. Trade financiers have been working to reshape the capital requirements defined in the context of trade transactions to more fairly reflect the favourable risk profile of the trade business.

There has been, though, analysis to suggest that both the cost and availability of trade finance will be adversely affected by the capital requirements. Bankers are giving consideration to the adverse impact of these capital requirements, not only on their own business, but on the commercial activities of corporate end-clients.

Just as trade financiers have an unprecedented opportunity to articulate and promote the value proposition around trade and supply chain finance, there is also an opportunity to demonstrate the ways in which trade and supply chain finance embody the trust and relationship aspirations of bankers more generally. There are several notable respects in which trade finance is particularly well-positioned to achieve a next level of client interaction and engagement, despite – and, perhaps, even through – some of the compliance and regulatory demands surrounding banking and trade finance today.

Discussion and dialogue related to the importance of trust and relationships in banking is a useful step forward in the “recovery” of the global financial system, but concrete action is the ultimate objective.

Trade finance – particularly in the MENA region – is well-placed to take a leading role in the advancement of the relationship/trust dynamic.

Cash And Trade Magazine For Cash and Trade professionals in the Middle East

Cash And Trade Magazine For Cash and Trade professionals in the Middle East

One comment