The Middle East has seen a massive surge in aviation industry growth. At the start of the 1990s, the region operated 218 aircraft with 100-plus seats and, by the beginning of this year, 875 had taken to the skies. MELANIE LOVATT looks at what made it all take-off and how it’s funded

The Middle East has seen a massive surge in aviation industry growth. At the start of the 1990s, the region operated 218 aircraft with 100-plus seats and, by the beginning of this year, 875 had taken to the skies. MELANIE LOVATT looks at what made it all take-off and how it’s funded

Record orders for new aircraft have been placed by airlines in the MENA region, and a further buying spree was expected at the Dubai Airshow in November.

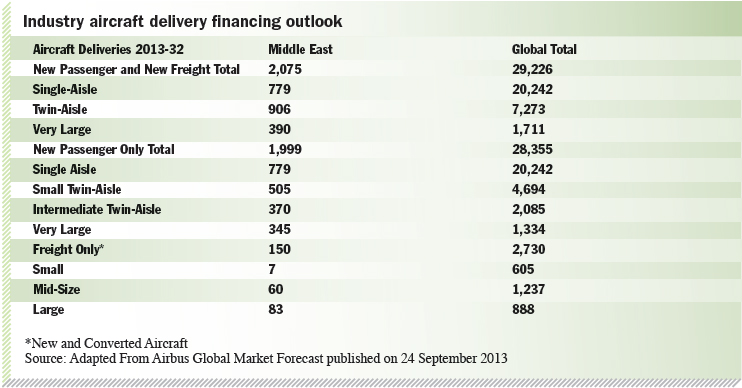

The main driver of such growth, which Airbus called “second to none” in its Global Market Forecast released in September, has been the push by Gulf countries to serve as hubs connecting not just the region, but major cities across the world. More than half of the Middle East’s aircraft are operated on medium-and-long-haul routes “highlighting the global strategy adopted by the region’s airlines”, commented the aircraft manufacturer.

Qatar campaigned to host the 2022 football World Cup, and along with its Gulf neighbours, is pushing to attract international sporting and cultural events. Gulf airlines have sought to raise their profile globally through sponsorship of top flight soccer clubs and celebrity tie-ins.

But, more significantly, their respective countries are using earnings from oil to diversify into petrochemicals, chemicals, and financial services not just at home, but via mergers and acquisitions in the region and abroad. And trade and commerce goals are within reach in part as a result of the growing aviation network.

Expansion had been confined to traditional carriers, but, after a relatively slow start, Gulf low-cost carriers or “budget airlines” are also getting a bigger slice of the business. They had less than one per cent of the market more than a decade ago, but now have 15 per cent and this share is growing.

Much of the Middle East’s fleet expansion is taking place in the Gulf, and its largest airline, Dubai-government owned Emirates, currently has 184 new aircraft on order and options on a further 100. Qatar Airways, the second largest, currently has orders worth more than $50bn for more than 250 aircraft, including Boeing 787 Dreamliners and 777s, Airbus A350s, A380s superjumbos and A320s.

Abu Dhabi’s Etihad Airways has seen remarkable growth since its 2003 inception and is now the region’s third largest carrier. Since 2011, when it took a 29 per cent stake in airberlin, it has expanded rapidly through acquisition. It bought 40 per cent in Air Seychelles, then Virgin Australia (now in the process of being increased to 19.9 per cent from 10 per cent) and almost three per cent in Ireland’s Aer Lingus.

This year it has sought a management contract for Air Serbia and, subject to final approval, 24 per cent of India’s Jet Airways. Etihad is also continuing to grow its own business, and is set to receive 15 aircraft this year. It has a further 75 on order over the next seven years, and has publicly said it plans to increase these orders to expand the fleets operated by its equity partners. It also extended a credit line to Virgin Australia in September, as the latter seeks to wrest domestic market share from Qantas Airways.

With the new high-tech giant aircraft costing hundreds of millions of dollars, even by Gulf standards the financing needs for this expansion are mind boggling. The good news for airlines on a growth trajectory is that in the currently low-interest-rate environment investors are seeking out value. In the wake of the credit crunch, they are wary of convoluted paper deals and showing a stronger appetite for transactions based on hard assets such as aircraft.

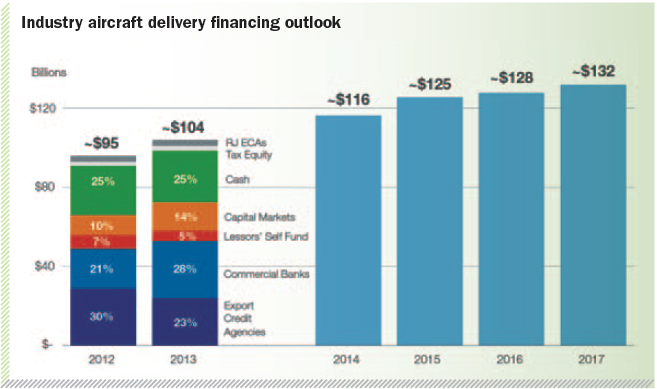

Boeing Capital, which supports the business units of US aircraft manufacturer Boeing by providing and arranging financing, forecast that this year export credit agency (ECA) financing would fall to 23 per cent of the $104bn global passenger aircraft financing market from 30 per cent of last year’s $95bn market. Commercial banks would take up some of this slack, climbing to 28 per cent from 21 per cent, with capital markets rising from 10 per cent to 14 per cent, cash contributions staying steady at 25 per cent and self-funding by lessors accounting for five per cent compared to seven per cent.

This is the financing pattern for Boeing and Airbus, the world’s dominant aircraft manufacturers, with the remainder (seven per cent in 2012 and five per cent in 2013) accounted for in financing for regional jets (this sector is also dominated by two players – Canada’s Bombardier and Brazil’s Embraer).

expected at the upcoming Dubai Airshow

Experts now see these global patterns playing out in the Middle East.

“One of the important features of aircraft financing by the Middle East airlines is how balanced it is among the various funding sources. They rely on every available source of liquidity, which is an important lesson they learned from the history of aircraft finance,” Boeing Capital’s senior director, Rich Hammond, told Cash&Trade. “That is, don’t be overly dependent on one particular funding market…Balance is the name of the game in the Middle East. We emphasise that diversity in the sources of liquidity is essential because all markets see disruptions from time to time,” he warned.

Commercial financing (via regional and international banks) has “come back into the picture for the Gulf players”, comments Frank Wulf, managing director, aviation finance, at transport specialist DVB Bank. Bankers have a strong appetite for Middle East aircraft finance, although there are some clouds on the horizon in the form of concerns that Syria’s ongoing civil war could lead to regional instability, he said.

Before the credit crunch that peaked in 2008, the Gulf’s top airlines saw very lean pricing. This jumped up during the global financial crisis for all airlines, but in particular the fallout from Dubai’s real-estate driven debt problems pushed up pricing for all of the emirate’s entities, including strong companies such as Emirates Airline. “Now we are slowly going back to the levels the market was at before the financial crisis,” said Wulf. But he notes that weaker airlines will struggle to match the lean pricing enjoyed by the top-tier names.

Financial turbulence looms

It is not all clear sky ahead and airlines will have to contend with some financial turbulence. There are concerns that the Basel III regulations being ushered in will act to push up bank pricing once again because long-tenored debt (aircraft financings can stretch out to a 12-year maturity) will carry a higher risk weighting for banks.

“Things are quite fluid. It’s still not clear what this will mean for aircraft financing,” Wulf told Cash&Trade. He is concerned that it could shorten the payback period for loans and this makes bank financing a more expensive proposition for airlines, and increases refinancing risk. “Personally, I don’t think Basel III will be helpful for the lending business,” he warns.

After the credit crunch, ECAs gained ground in many sectors, including aircraft. But ECA use is now slipping after the OECD’s 2011 Aircraft Sector Understanding (ASU) elevated ECA pricing, particularly for up-front fees, which can be as high as 12-14 per cent, notes Wulf.

The new ASU was “grandfathered” in and its full effects started to be felt from January this year. ECAs support manufacturers of aircraft and parts in their own countries by offering guarantees, while banks supply the underlying funding, although some ECAs, such as the Export-Import Bank of the US (US Ex-Im) are increasingly able to provide direct funding.

It may seem counter intuitive that the ASU was ushered in despite lingering ill effects of the global economic and banking crises.

However, cheaper borrowing from ECAs (the margins are determined by the rating of the ECA’s home country) has led to some market distortions, say critics. Some airlines assert their own government agencies are making financing cheaper for foreign competitors. In the US Delta Airlines, the world’s largest, brought legal action to stop US Ex-Im’s support of US-manufactured aircraft sales to Air India.

In June, the US Court of Appeals in Washington DC rejected Delta’s request. While it asked Ex-Im to explain its decision, it chose to leave the financing in place. Thus, given that airlines are regarded as strategic industries, global trade agreements such as the ASU have been aimed at keeping the playing field level.

“ECAs have played a fairly modest role in supporting deliveries to the Middle East carriers and in large part that had to do with diversification of their financing sources,” explains Boeing Capital’s Rich Hammond.

“Middle East airlines have developed a very balanced financing profile, and they have used export credit only when necessary. This can occur when they ‘max out’ all of the commercial markets, where the commercial markets have concentration or exposure limits.” At this point, Middle East carriers shift and rely for a “top up” on export credit, he said.

Francois Collet, Airbus’ vice-president, structured finance, says “new export credit rules and premium pricing have provided an incentive to airlines to find alternative sources,” suggesting that ECA-supported deliveries will fall from 22% in 2012 to 15-20% in the near future.

ECA transactions signed this year in the region include Air Arabia’s deal in September with KfW IPEX-bank for a 12-year facility guaranteed by German ECA Euler Hermes for four Airbus A320s. This followed deals the Sharjah-based company signed for one A320 in April and another in August. Air Arabia, MENA’s largest low cost carrier, announced a strong performance for the first half of this year, allowing it to focus on further growth. It currently operates a 31-strong fleet of A320s, and has placed orders for a further 40.

Smoothing the flight path

The headwinds of Basel III and the ASU are encouraging more players to steer to capital markets and leasing (lessors themselves are expected to source most of their financing from banks and capital markets). Boeing Capital forecasts that more than half of the world’s airline fleet will be leased before the end of the decade, up from the current 40 per cent share.There have been few lessor direct deliveries (speculative orders that they then place with Middle East airlines) because lessors traditionally invest in single aisle models and Middle East airlines have ordered more wide body aircraft and preferred to own these, said Collet. However, lessors are now “switching interest towards wide body aircraft” and airlines “need the leasing flexibility for fleet operation, capital expenditure management and overall balance sheet position,” he asserts.

Wulf estimates that the percent of leased aircraft in the Gulf is growing more rapidly than the global average as a result of the expansion of low-cost carriers. Fly Dubai, for example, has most of its fleet on operating leases.

Conventional carriers have also recently finalised leasing deals. In June, Los Angeles based Air Lease Corporation announced a long-term lease agreement with Etihad Airways for one new Boeing 777-300ER aircraft, scheduled for delivery in September 2014.

This follows ALC’s April deal with Etihad for a new Airbus A321-200 aircraft with sharklets (wing tip modifications aimed at reducing drag) for delivery in April 2015. “Etihad is a successful and rapidly growing airline that has a large delivery stream of aircraft on the way. Market recognition of their success is a reflection of the strong response by financiers to their RFPs [request for proposals], whether through leasing, commercial bank debt or other structures,” said Hammond.

Etihad’s financing strategy is diversified, and whilst it has recently raised most of its cash outside the region, when conditions are right it will use local financiers. In April, it closed its first deal with a regional bank in five years, securing a $359m loan for two Boeing 777-300ER planes with the UAE’s First Gulf Bank.

Other local funding sources are being tapped. State-held Qatar Airways conducts much of its financing through leasing via other Qatari government entities. It will sometimes use external sources of funding, but usually these are finely priced and by and large mostly appeal to the country’s domestic banks.

The Gulf’s sovereign wealth funds, and other

financing units, are expected to make further inroads into aircraft financing. Abu Dhabi conglomerate Mubadala created Sanad Aero Solutions to focus on leasing of aircraft engines and components because it saw a gap in the market. Sanad signed a 10-year agreement in March valued at more than $125m for the sale and lease back of some of Etihad’s key component spares.

The Gulf airlines have helped engineer some innovative capital market financing structures. Emirates airline and aircraft lessor Doric received awards last year for opening the capital markets to non-US issuers in the aviation industry. And enhanced equipment trust certificates (EETCs) provided financing for four Airbus A380s on long-term lease to Emirates.

The Doric Alpha EETCs are not only the first to use A380s as collateral, but also the first certificates by a non-US issuer in a long time. The $578.5m issue in June 2012 was three times oversubscribed and effectively allowed Emirates to tap the US capital markets without a rating from international credit agencies.

In July this year, Doric and investment fund Nimrod Capital sold shares valued at $335m backed by leasing revenue from four Airbus A380s operated by Emirates.

Emirates is looking to make another foray into the capital markets, and considering the issue of Sukuk as it seeks to raise around $4.5bn to fund aircraft purchases for the next financial year starting 1 April 2014. The company issued $1bn in 12-year amortising Sukuk and $750m in 12-year amortising conventional bonds earlier this year. It will weigh costs when deciding what funding to use, and any approach to the capital markets will depend on favourable market conditions.

“We explored new funding options in 2012-13 as a way to broaden and diversify our investor base. These included three different, unsecured bond issues. All were heavily oversubscribed – a sign of investor confidence in the strength of the Emirates business model,” commented Emirates chairman and chief executive officer Sheikh Ahmed bin Saeed al Maktoum, in the company’s latest annual report.

Over the past two years capital markets have tripled as a funding source for new aircraft deliveries, says Rich Hammond. “This is a reflection of global investor appetite for aircraft as collateral. When looking at the historical performance of aircraft, whether over the last few decades or through the recent financial crisis, you’d be hard pressed to find any asset class that has done as well,” he said. “As a result, it is attracting a lot of interest, and real money, to the aviation sector.”

Cash And Trade Magazine For Cash and Trade professionals in the Middle East

Cash And Trade Magazine For Cash and Trade professionals in the Middle East

One comment